This blog was written by Kirsty Newman, Programme Director for the RISE Programme, based in Oxford Policy Management (OPM). It was originally published on the RISE website on 18 March 2021.

In the last week in the UK, there has been an outpouring of stories from women about the discrimination, harassment, and violence that they experience just as a result of being women. The UK situation has followed the same pattern that has been seen in countries across the world—a high-profile act of violence horrifies a nation but also triggers an anguished discussion about just how commonplace the experience of gender-based oppression is. It makes me feel anger—or in fact rage. And it galvanises my resolve to work to protect and empower women however I can.

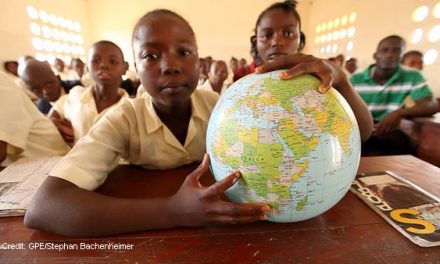

Given this, and given the fact that I work in global education, it is perhaps not surprising that I am a big fan of the focus on girls’ education. Education is clearly not a panacea against violence. But it can empower and enable girls and women to take back control and to gradually fight back against entrenched systems of oppression.

But, I do worry that because we see education as a solution to gender inequality we sometimes make the mistake of thinking that gender inequality in education is the biggest priority. In fact, while it is undeniably a global disgrace that vast swathes of the world’s girls are not learning even to read, girls’ foundational learning levels are generally not worse than boys’. In most low- and middle-income countries learning outcomes at primary school are dreadful for both boys and girls. If anything, girls tend to slightly outperform boys—but the differences are small. And because of this, focussing on getting equality in learning outcomes within developing countries should not be our primary focus.

We need to think about the absolute outcomes we want for girls (i.e. learning) rather than the relative outcomes (i.e. performance compared to boys). And if we want girls to learn, we need to focus on the education system they are part of. We need to consider whether the system is set up to enable learning—and in particular whether key foundational skills are being built in the early years. We need to understand whether teachers are supported and incentivised to deliver effective teaching that is matched to the learning levels of their students. And we need to check whether a lack of learning triggers remedial action at individual, classroom, or school level.

Putting this focus onto the education system will of course benefit boys as well as girls—but surely that is not a bad ‘side effect’? The alternative—to focus only on interventions that disproportionately benefit girls—means that we will not be tackling the key issue of low foundational learning levels. And that would be doing a massive disservice to girls.

RISE blog posts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.