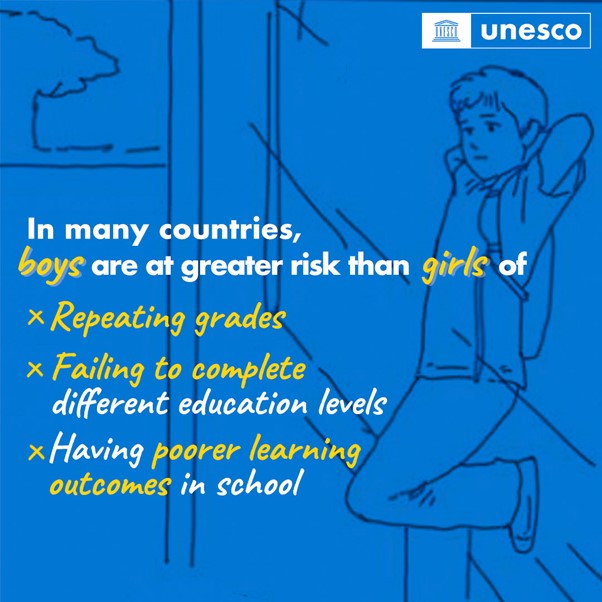

On 7th April 2022, UNESCO organised a webinar in partnership with Promundo and The Commonwealth Secretariat to launch the new report: ‘Leave no child behind: Global report on boys’ disengagement from education’. This report shows that, in many countries, boys are at greater risk than girls of repeating grades, failing to complete their education and of having poorer learning outcomes. You can read a brief ‘what you need to know’ about the report here.

On 7th April 2022, UNESCO organised a webinar in partnership with Promundo and The Commonwealth Secretariat to launch the new report: ‘Leave no child behind: Global report on boys’ disengagement from education’. This report shows that, in many countries, boys are at greater risk than girls of repeating grades, failing to complete their education and of having poorer learning outcomes. You can read a brief ‘what you need to know’ about the report here.

The launch event was officially opened by Stefania Giannini, Assistant Director-General for Education for UNESCO, and a global overview provided by Maki Katsuno-Hayashikawa, Director of the Division for Education 2030, UNESCO. She informed participants that despite tremendous progress in enrolment over the last 20 years, estimates indicate that of the 259 million children and youth currently out of school, over half of these – approximately 132 million – are boys.

Webinar participants then heard from different stakeholders in two panel discussions. The first covered challenges faced by boys in regional and select country contexts, while the second focused on policy responses and good practices to re-engage boys in education. The event can be watched in the video below.

Catherine Jere of the University of East Anglia, one of the authors of the report, provided a regional perspective. Across regions, there are historical patterns in boys’ disadvantage that have changed little in the last two decades, but also emerging trends that require closer attention. For example, gender disparities in secondary education at the expense of boys have persisted in Latin America and the Caribbean. Despite some improvement in participation in lower secondary, boys are far less likely to complete a full cycle of secondary education. Exacerbated by poverty and the need to work, a culture of machismo, peer pressure and disillusionment with schooling can lead boys into an early exit from education.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where typically, girls have faced severe disadvantage in terms of school entry, enrolment and completion, evidence is emerging that in several countries boys are now falling behind girls – reflected in a ‘reversal’ of these gender gaps. This includes countries such Burkina Faso, Burundi, the Gambia, Rwanda and Senegal – again with the greatest disadvantage among the poorest. In Southern Africa (countries including Lesotho, Namibia and Botswana), where traditional cattle-herding pulls boys out of school early, gender disparities are particularly severe. In 2019, just 76 boys for every 100 girls were enrolled at lower secondary level in Lesotho, which has changed little since 2000.

A phenomenon that has attracted considerable attention in high-income countries in Europe and North America over the decades is boys’ underachievement – including the large and persistent gap in reading skills. In the first panel discussion, François Staring discussed key lessons learned from the recent EU Study on Gender Behaviour and its Impact on Education Outcomes.

Countries in the Arab States show some of the largest disparities at boys’ expense in terms of learning outcomes. Low performance at school both reflects and contributes to their disengagement and dropout. Natasha Ridge, of Sheikh Saud bin Saqr Al Qasimi Foundation for Policy Research in the United Arab Emirates, highlighted key factors that lead to boys’ early exit from education.

Participants were privileged to hear from Lesotho’s Minister of Education and Training, Mamookho Phiri, and Fayval Williams, the Minister of Education, Youth and Information in Jamaica, both of whom shared valuable insights into the challenges and successes of policy and practice for re-engaging boys in education. Helena Reuterswärd, Senior Policy Specialist for Education with Swedish International Development Cooperation shared further reflections on strategies required to address boys’ disengagement and Gary Barker, CEO of Promundo, challenged the audience to consider the importance of addressing gender norms, and stereotypes that place expressions of masculinity at odds with schooling, making education unpopular with boys.

Worryingly, this report’s analysis shows governments’ very limited attention to issues of boys’ disadvantage globally. Comprehensive policies to address the issues are rare, and predominantly found in high-income countries. Few low- or middle-income countries have policies in place to improve boys’ education, even in countries with severe disparities at boys’ expense. The report’s review of policies from 19 countries found only 4 – Bangladesh, the Gambia, Jamaica and New Zealand – had education policies specifically targeting boys. Jamaica has been particularly successful in improving the situation for boys with a variety of strategies including financial support for boys from poorer households: where previously fewer boys than girls were completing secondary education, by 2019 gender parity had been achieved.

Targeted action to improve educational opportunities for boys not only benefits boys’ learning, employment opportunities, income and well-being, but can also be instrumental in achieving wider economic, social and health outcomes, including gender equality. Educated men are more likely to demonstrate more gender-equitable attitudes and practices and support gender equality policies.

Discussants agreed that supporting boys does not mean that girls lose out, or vice-versa. But rather that equitable and inclusive education opportunities benefit both girls and boys, and is, ultimately, transformative.

Several country case studies are provided – for Kuwait, Lesotho and United Arab Emirates. Personal stories show how two boys managed to continue their education – José Miguel from Guatemala and Ahmad from the United Arab Emirates.

A blog, ‘Education increasingly becomes a boys’ problem at high cost’, also highlights some of the key messages from the report on boys’ disengagement.