This blog was written by Margo O’Sullivan, independent consultant and CEO of Power Teachers.

Prior to COVID-19, 6 out of 10 children globally and 9 out of 10 children in Sub-Saharan Africa, were not learning. With the significant learning losses during the pandemic, even more children are at risk of learning poverty and lifelong poverty. COVID-19 school closures highlighted further the issues around learning and the critical role of teachers, with a surge of appreciation for teachers worldwide. Pre-pandemic, the evidence was overwhelming that teachers are the key to children’s learning, in particular, pedagogical effectiveness, leading to more inclusion of teacher support strategies in interventions, in particular professional development, which are continuing now that schools have re-opened.

The success of teacher support interventions in improving learning are ultimately dependent on teacher implementation in the classroom. However, teacher attendance, the most basic implementation factor, is too often overlooked – if teachers are not in school, or when in school, not in class teaching, failure to improve learning is inevitable.

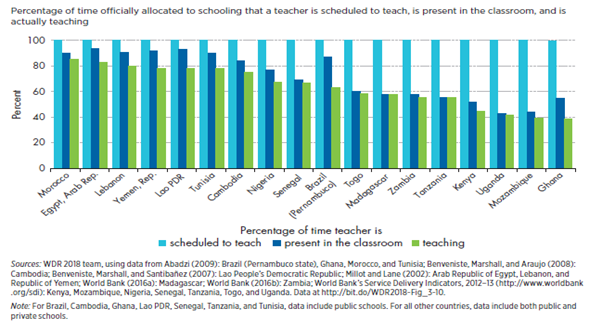

UNICEF Innocenti’s 2020 study on teacher absenteeism in 19 countries in Eastern and Southern Africa found teacher absenteeism rates ranging from 15% to 45%. These findings reflect the findings from an earlier study in 7 African countries, which highlighted that on average primary students received less than 2.5 hours of teaching per day. The 2018 World Development Report collated evidence from countries globally, highlighting that the situation in Africa is also reflected in countries in South America, South Asia, and the Middle East (see Table 1). This is a crisis issue, yet, it still fails to receive significant attention.

Table 1. A lot of official teaching time is lost

With teacher pay comprising at least 80% of recurrent budget in most countries, this is leading to huge inefficiency and wastage. Muralidharen et al. calculated the fiscal cost of teacher absenteeism at $1.5billion each year in India and Uganda. In 2017, she revisited the rural villages surveyed in 2006 and found only a modest reduction in teacher absenteeism from 26.3% to 23.7% on average. Teacher absenteeism and reduced time on task wastes valuable financial resources, short-changes students and is one of the most cumbersome obstacles to improving learning.

There are a number of reasons to explain this systemic teacher absenteeism. The most often cited reasons include poor accountability of managers and inspectors, illness, and poor working and living conditions of teachers, ultimately impacting negatively on teachers’ motivation. A key and overarching factor in teacher absenteeism is the disconnect between the demands of the profession and systemic support to teachers to meet these demands. Teachers are expected to perform as professionals but the education systems are failing to treat them as such or provide a professional culture for them. Pay, respect and working conditions are poor and have declined over the last few decades. Yet, systems still want more from teachers, not least during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, but teachers also deserve and want more from the systems that employ them.

There are a number of reasons to explain this systemic teacher absenteeism. The most often cited reasons include poor accountability of managers and inspectors, illness, and poor working and living conditions of teachers, ultimately impacting negatively on teachers’ motivation. A key and overarching factor in teacher absenteeism is the disconnect between the demands of the profession and systemic support to teachers to meet these demands. Teachers are expected to perform as professionals but the education systems are failing to treat them as such or provide a professional culture for them. Pay, respect and working conditions are poor and have declined over the last few decades. Yet, systems still want more from teachers, not least during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, but teachers also deserve and want more from the systems that employ them.

Addressing teacher motivation and its related elephant in the classroom, teacher absenteeism, will be challenging however. If we are to effectively address learning losses and improve learning outcomes, we must embrace the challenge and take teacher motivation and teacher absenteeism into account in all interventions focused on improving learning. Otherwise, we will continue with interventions and reforms that will fail to lift many of the world’s most disadvantaged children out of ongoing learning poverty and lifelong poverty.