This blog was written by Dr Lizzi O. Milligan, Reader, and Dr Laela Adamson, Researcher, in the Department of Education at the University of Bath. Together they are co-editors of a new policy brief ‘Girls’ education and language of instruction’, produced by the University of Bath Department of Education, Institute for Policy Research (IPR) and the UK government Girls’ Education Challenge. This blog was originally published on the IPR website on 1 June 2022.

Iza, a fifteen-year-old girl who attends secondary school in a rural district of Rwanda, sits in a history lesson where she is learning about the causes of the French Revolution. She is tired, having got up at 5.40am to help with family chores, but tries to pay attention and follow the teacher’s words.

She does not understand a lot of the content but is scared to ask the teacher in case she uses the wrong words in English. She is happy when he uses some of her own language, Kinyarwanda, to translate the key vocabulary and when she has the chance to talk to her friends in a group activity. She hopes to pass her upcoming examinations and spends a lot of her spare time memorising content in English in the hope this will be enough to get by.

Iza’s story is not a solitary case.

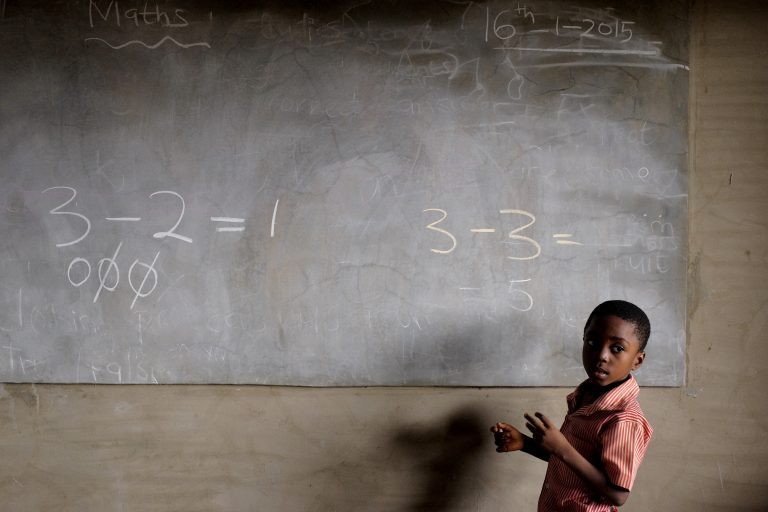

Globally, millions of primary and secondary school children learn all subjects in a language that they do not fully understand. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank have estimated that as many as 80% of learners do not have access to learning in languages they know best. Decades of evidence, mainly from African researchers, has shown that this has a detrimental effect on learners’ classroom participation and their learning outcomes.

In a new extended policy brief, we have brought together a range of evidence that shows this detrimental effect for girls, particularly those most at risk of drop-out, poor performance and from groups that are socially and economically marginalised.

What does this mean for the girls’ education agenda?

The recent publication of the new UK international development strategy reaffirmed the UK’s commitment to girls receiving 12 years of quality basic education as a key priority. This comes after the G7 group of nations last year agreed to a target of 40 million more girls into basic education in low and middle-income countries.

Many countries have prioritised girls’ education access and outcomes. However, what language girls learn in has rarely been part of policy discussions (see also, Benson 2005). If we are to enable all girls to access and progress in quality, equitable education, the language of instruction must be considered as a policy priority.

Why focus on language of instruction?

The extended policy brief highlights three key reasons why language of instruction needs to be an important consideration for girls’ education priorities:

- In the early years of schooling, children’s access to good foundational literacy outcomes are impacted by the language they learn in. As Rona Bronwin, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Education Advisor, highlights in the foreword for the policy brief, language is ‘an essential precursor to gaining foundational skills’ and needs to be considered as a key priority to ‘improve transitions at key points in primary and secondary’.

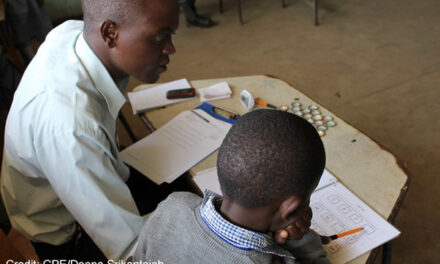

- Being able to listen, talk, read and write in the language of instruction is needed for girls to access new subject content and make meaning of that new knowledge. This is particularly important in countries, such as Rwanda and Kenya, where the curricula are based on developing competencies, including critical thinking and problem solving. Throughout the policy brief there are numerous examples of girls excluded from such meaning-making in and out of the classroom because of the language of instruction.

- The policy brief does not only focus on the role of language in girls’ educational outcomes. We also highlight the ways that learning in an unfamiliar language impacts on girls’ socio-emotional experiences of school, including discussions of girls’ feeling of shame and lack of confidence.

Is this only an issue for girls?

The three key points listed above are clearly not only an issue for girls. However, the evidence that we have collated, which includes significant data from across the Girls’ Education Challenge, suggests that language demands intersect with gendered socio-cultural norms to particularly burden girls. Crucially, we also see how these intersecting burdens affect some girls more than others, with the issues related to an unfamiliar language compounding existing educational, cultural and socio-economic barriers to learning.

Making changes to the language that children learn in could dramatically improve the most marginalised girls’ educational chances. And as research by the REAL Centre for CAMFED has highlighted, prioritising educational reforms that target the most marginalised girls can improve the quality of education for all children.

What next?

We were recently asked what our priorities would be for policy and practice going forward. We recognise the current language of instruction policy trajectories in many countries which seem to be only going in one direction; for example, in Rwanda with the recent shift to English from the first day of schooling.

In light of these trajectories, we suggest the importance of language-supportive pedagogies and targeted language-of-instruction development before and after the point of transition to that language. Alongside this, we will always advocate for education system reform across Sub-Saharan Africa so that classrooms are spaces which reflect the rich multilingual realities of girls’ lives and where girls can make meaning in the languages and knowledges that they already have.

Within the wider socio-economic context of girls’ lives in 2022 – two years into a pandemic which has had a profound impact on children’s educational experiences in every country of the world – millions of girls have not returned to school; and many never will. The evidence that we have collated very clearly shows that language of instruction is an additional barrier to girls’ learning. Paying attention to this barrier in pandemic educational recovery and in girls’ educational planning is needed for Iza, and for so many millions more, across Sub-Saharan Africa.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath. Download ‘Girls’ education and language of instruction: An extended policy brief’ edited Dr Lizzi O. Milligan and Dr Laela Adamson, and learn more about their research on girls’ educational experiences in English medium Rwandan basic education.

This is a great post and raises a hugely important issue.

But Rwanda is an unusual case for Africa: there is only one mother tongue spoken by the large majority of the population. Even the minority Batwa people mostly also speak Kinyarwanda. A much more typical scenario for that part of the continent (and others) is for example the situation in nearby South Kivu province of DRC, where several different languages are spoken in homes and communities, with Kiswahili used as a lingua franca (mainly by adults), and French as the school LOI.

Your emphasis on “the importance of language-supportive pedagogies and targeted language-of-instruction development” is therefore critical. But unfortunately the tendency post-Covid has been towards increased emphasis – driven by misplaced donor investment – in the chimera of literacy with comprehension before children are ready for it. The so-called “learning crisis” is not actually a crisis in learning, nor even in literacy: it is a crisis of ignoring oracy. Classroom talk is valued in the primary school classrooms of rich monolingual countries, but largely ignored, or even discouraged, in classrooms in the countries where it is most needed. No-one, child or adult, can read with comprehension a text in an unfamiliar language. The focus needs to shift from early grades literacy to early grades oracy, in both mother tongue and LOI.