This blog was written by Rachel Wilder and Terra Sprague at the University of Bath, Jo Westbrook at the University of Sussex and Ben Durbin, Raspberry Pi Foundation. All of the authors are members of the UKFIET community and are involved in organising our Conversations for Change events.

In December 2022, the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) published compelling proposals for education systems to respond to climate and environmental crises in its new position paper, ‘Addressing the climate, environment, and biodiversity crises in and through girls’ education’. Many of these proposals align with ideas advanced at ‘Conversations for Change: The Future of Education for Global Climate Justice’, an event hosted by UKFIET a few weeks earlier, which brought together policy-makers, academics, global NGOs and education practitioners to discuss critical concerns and collectively envision the future of education for global climate justice.

The resounding message that emerged from the UKFIET event is that the status quo is unacceptable: education needs to change. In this blog, we welcome FCDO’s commitment to delivering this change, and offer recommendations for where more needs to be done.

A welcome commitment to change

The FCDO paper provides an important statement of intent, recognising the urgency of the climate crisis, the equal importance of environmental and biodiversity issues (adopting the term ‘climate and environmental change’), and the need for immediate and concerted action across disciplines and sectors.

Aligning its policy goals on education and climate has the potential to accelerate progress on both fronts. By adopting integrated, multi-sectoral and inclusive approaches, education can help address climate injustice and reduce vulnerability to weather-related disasters (see Table 1 of the FCDO Position Paper). This includes the role of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in addressing mitigation through sustainable local environmental practices, and in promoting reduced consumption / emissions (Box 8).

It is noteworthy to see the UK, a donor and global policy leader in education, recognise that current funding for education systems to respond to climate change – at best 0.03% of all climate finance – is completely insufficient. Much more will be needed to realise the changes necessary for education to support transitions to more socially just and environmentally sustainable futures. The paper includes some welcome suggestions for action that can be taken, seeking ways to recognise education investment as climate action and increasing the focus on education as part of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions.

A key theme for FCDO is the disproportionate impact of the climate crisis on women and girls and those with disabilities, aligning with its wider focus on girls’ education. We welcome the attention given to those most vulnerable, and on the impact of climate and environmental change in exacerbating existing inequalities (Figure B).

The paper recognises the importance of the work of communities and young people to act on climate change and aims to “empower those worst affected by the impacts of climate change and centre their voices as leaders and agents of change”. This agency is also an important part of alleviating eco-anxiety that can arise simply through a knowledge-transfer approach to ESD. Although we would like FCDO to go further on these points (see below), we welcome its recognition of the role of ESD in advocating for ‘increased ambition’ by governments and businesses (Box 8).

Finally, FCDO makes some hopeful statements on curricular and pedagogic approaches that enables positive change:

“The concept of ‘global’ climate change curricula should thus be treated with caution. Content should be accessible, actionable, and contextually relevant; be taught at an appropriate age; encourage problem solving; and be centred around hope to awaken students’ agency to effect change.”(p. 20)

The paper acknowledges that ESD should respond to children and young people’s local contexts, for example by including traditional practices for sustainability, and that existing curricula are often overloaded, which means there is little time to consider local context and localised responses (p. 20-21). These apparently radical ways forward are strongly welcome, and reflect the need to connect teaching to children’s lived realities.

Whilst there are many reasons to be positive about FCDO’s paper, we have also identified some gaps and problematic aspects. Drawing on the proposals for educational transformations developed by participants at the ‘Conversations for Change’ event, there are four areas to highlight.

- Focus on people and communities most affected by crisis

FCDO’s rationale for focusing predominantly on girls’ education is that if education can be improved for the most marginalised girls, it will be better and more inclusive for everyone (p. 9). It argues for ‘integrated solutions’ to be found to girls’ education and addressing the climate and environmental crisis. While appreciating that the broader intention is for inclusive education, the narrative around girls still serves to put them at the centre. There is a danger that this will inadvertently divert responsibility for tackling climate change onto vulnerable girls who have a multitude of burdens placed on them already, whilst simultaneously neglecting their perspective on the issues affecting them.

The FCDO paper is a missed opportunity to outline how the most affected groups could be involved, in a sustained way, in making decisions about overarching policies that guide stronger responses to climate and ecological crises affecting them, as well as about local adaptations, educational interventions and transitions. As we wrote in our Call for Action following our Conversations for Change event in November 2022: ‘The likely outcome is that global efforts to tackle climate change will further entrench existing injustices and inequalities’.

The FCDO paper is a missed opportunity to outline how the most affected groups could be involved, in a sustained way, in making decisions about overarching policies that guide stronger responses to climate and ecological crises affecting them, as well as about local adaptations, educational interventions and transitions. As we wrote in our Call for Action following our Conversations for Change event in November 2022: ‘The likely outcome is that global efforts to tackle climate change will further entrench existing injustices and inequalities’.

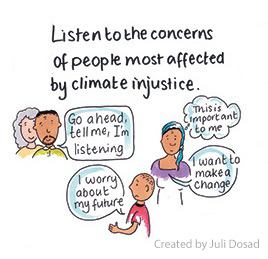

A key recommendation emerging from our event is that education transitions have a much larger focus on people and communities who are most affected by climate and ecological crises, not just the girls and marginalised children who live within such communities. These voices are conspicuously absent – a critique often, and justly, made of international decision-making processes for climate change agreements and financing conversations.

- Give greater attention to experiences of schooling, pedagogy and curriculum

Despite recognising a need for curricula and pedagogic interventions that will transform education into a vehicle for sustainable development, the suggestions made in the paper are unlikely to achieve this. FCDO uses this position paper to reiterate their goal of getting 20 million more girls to read a paragraph, through ‘structured pedagogy programmes’ (p. 20) as if this is a magic bullet that will solve the climate crisis. There is a danger that this condones the continued use of content-heavy curricula that leave little space for student voice nor teacher autonomy. Such an approach is at odds with the more open, democratic and localised pedagogies appropriate for the critical and engaged thinking and actions needed for climate change.

As discussed at the Conversations for Change conference, there was instead consensus for curricula that can be localised by teachers and local actors to reflect the lived realities of students, and enable them to access school and learn knowledge and skills relevant to their communities – and which will include learning to read relevant texts. Curricula should respect and privilege indigenous knowledge, encourage intergenerational knowledge sharing and break down disciplinary boundaries.

Furthermore teachers should teach the root causes of climate change and the consequent social injustices, and should encourage student voice and political awareness, empowering students to take actions they judge to be important and relevant to them. This has major implications for overhauling teacher education, giving trainee teachers such localised experiential learning and opportunities to study with climate change scientists, community actors and climate activists. Growing a garden and planting trees with students is a starting point, but is insufficient without teachers’ political and social engagement.

Furthermore teachers should teach the root causes of climate change and the consequent social injustices, and should encourage student voice and political awareness, empowering students to take actions they judge to be important and relevant to them. This has major implications for overhauling teacher education, giving trainee teachers such localised experiential learning and opportunities to study with climate change scientists, community actors and climate activists. Growing a garden and planting trees with students is a starting point, but is insufficient without teachers’ political and social engagement.

In order to address the climate and environmental crisis to greatest effect, we encourage FCDO to support such curricula, complemented by pedagogies that get children moving as well as talking and debating; take place anywhere, anytime, removing the walls and furniture of the conventional classroom, and blurring inside/outside spaces; create urban safe spaces and child-friendly cities for children to learn and play in; and allow children to experience climate change and voice their concerns.

- Recognise education for social and political transformation

A further significant gap is the idea that improving education systems to support social change in the interests of environmental protection is a technical matter of appropriate interventions, programmes and skilled, supported educators. The root causes of climate change from fossil fuel emissions, pollution and agriculture from the Global North are obscured by the position paper. Instead, getting girls and boys to school and learning is seen as a form of redemption, or at least mitigation. Adapting to this man-made crisis, and coming up with ‘new solutions’ side-steps recognition of the damage done by the Global North, and the more urgent need for behaviour change by the wealthier few and a shift to green economies.

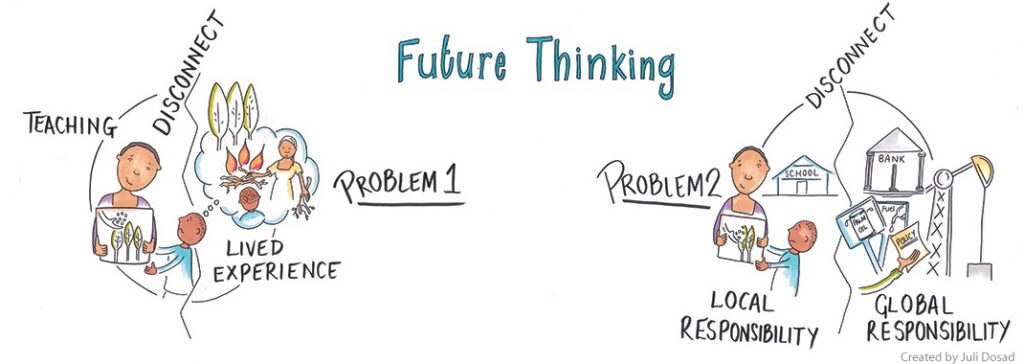

While there is some welcome recognition (Box 8) that the Global North has responsibility for lowering consumption levels and therefore behaviour change, overall the position paper constructs an unequal binary of responsibilities with mitigation carved out to the Global North and adaptation to the Global South (Box 6). This reduces the agency of those activists whose voices were clearly heard at our Conversations for Change conference. The paper also depoliticises the causes of climate change throughout, exacerbating that disconnect between local and global responsibility for climate change.

Participants at the Conversations for Change event soundly voiced a collective concern and demand for education systems that are socially and politically transformative. We are in a planetary crisis, and nothing less than a total rethink of the current model of schooling that excludes so many will do, if we are to change course and advance environmental survival and flourishing.

- Allocate new funding

As recognised in the FCDO paper, education is embarrassingly under-funded when it comes to responses to climate crises. 0.03% of climate change financing is not enough for education systems to adapt. We call on the UK government to take the lead in allocating new funding for education transformations for just and sustainable educational futures.

FCDO has made an important statement of intent with the publication of this position paper. In his foreword, Minister of State, Andrew Mitchell, writes:

“Time is running out to ensure every child has the opportunity to fulfil their extraordinary potential. The fate of our children and our planet are one and the same. Now is the time to ensure the future is bright for both.” (p. 4)

As FCDO’s positioning translates into decisions about funding, policies and programming, we offer the reflections in this blog as essential to ensuring transformative change delivers this bright future.

You can read more about ‘Conversations for Change’ here:

Conversations for Change – Day Conference recap and resources

Just and Ambitious – A Call for Action

The images in this blog are credited to Juli Dosad and are part of a larger piece of visual work which reflects the main messages from the ‘Conversations for Change’ Day Conference.

Interested in or already working on this topic? You can get involved in the establishment of a new network for those advancing the work of Education for Climate Justice by registering your interest here.

You can read other content on the UKFIET website relating to climate change and climate justice here.