Numerous dignitaries, academics and salespeople (but thus far no robots) are flocking to copious conferences, sundry seminars and voluminous workshops focussed on Education and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Reciting the same prosaicisms and expressing identical anxieties, few explore the fundamental issues in any depth or creatively address the immense opportunities on offer. In this blog, Mike Douse outlines how AI might best be managed and mobilised to enable equitable, third millennium-appropriate and affordable lifelong education worldwide.

In recent months, I have attended four events addressing Artificial Intelligence (AI) in relation to education. Three virtually, and one in the flesh; one focussed upon ethics and equality; another on AI and higher education; all four encompassing regulatory mechanisms and the role of governments. Alongside me were assorted excellencies, profusions of professors, vigorous venders of various applications, and polished representatives of national and international organisations.

Most presentations incorporated the idea that AI offers both opportunities and threats, with many failing to go much beyond that fairly obvious observation. At each event I asked the question: ‘Are any robots participating in this conference – have machines been invited?’ In all four instances, this was responded to light-heartedly and in the negative. And yet it is a serious question, as a small number of participants recognised in discussions with me afterwards. If we are to reap optimum benefits from AI, their creative participation alongside us humans is surely feasible and undeniably desirable.

An impressive variety of AI applications was on display. While, of course, I was unable to examine them all in any detail, it seemed that many had been created without the involvement of teachers, let alone of learners, and few seem to have been rigorously piloted. From teaching machines in the 1960s, through expensive, maintenance-requiring, space-invasive language laboratories, to the more recent (yet now obsolete) ‘computer rooms’, malign manufacturers have attempted to milk the education market. With AI applications and systems, with potentially sky-rocketing costs, and where content ownership and cultural assumptions are contested, it is especially important that technological determinism be identified and rejected. [Much as I must resist making broad generalisations based on relatively small samples.]

But a certain concern is that many of the advocated AI approaches were founded upon an assumption that education would remain much the same as it is now, sculpted for an industrial society, designed for a disconnected world, based upon herding learners into designated places, teaching at them, applying externally imposed curricula, and determining their life chances partly upon their ability to regurgitate irrelevancies. For schools remain fossils from a time before the internet, and certainly before AI, built before the vast library of human knowledge became instantly accessible at our fingertips, through the computers on our desks and smartphones in our pockets.

Not one speaker, in any of the sessions that I attended, at any of these four events, acknowledged that education is undergoing a fundamental transformation, necessitated and enabled by contemporary technology. There seemed to be an unquestioned belief that AI would be incorporated into a static world of buildings called schools, content called curricula, knowledge fonts called teachers and sorting mechanisms called exams. Much as if in the mid-15th century, when Johannes Gutenberg had just developed movable type printing technology, all of the assorted theologians, teachers, scholars and sundry middle-ages sages attending a conference on ‘Education and Books’ just assumed that the latter will have no effect upon the former, let alone upon the world at large.

And they might be forgiven for that lack of vision – after all, those were still the Dark Ages. But there can be no such excuses for us third millennia sophisticates, bombarded as we are with ‘future of education’ not to mention ‘future of society/ world/ universe’ despatches on hourly bases. My own view is that education in the coming times will be learner-led, with the preparatory years devoted to enabling all to direct their own learning from early secondary onwards, with schools as processes, and with fewer but better-paid teachers in exciting new supportive roles. Other prognostications are permissible but the one thing that Education 2040 will not be is Education 2023: assuming such steadfast perpetuity represents not so much AI as human short-sightedness.

Where lies the blame for this visualisation deficiency? Not so much with conference organisers and presenters, still less with participants: we were all schooled in rule-following and in accepting authority-defined entities as given. It is the vision that is faulty and, when that is clouded over, and the blinkers firmly on, and the only spectacles available are of the wrong prescription, it is little wonder that we stumble out from the incorrect starting-point. The paramount need now is to agree upon where we are going as opposed to assuming that we will always stay where we presently are.

What is to be done? Surely we must discuss and decide what forms of education, to what ends, in which likely settings, are most desirable and then determine how best, in creative tandem with AI, to get there. [Needless to say, machines should participate in those consultations.] Suppose, for example, the agreed goal was to comprise, achieve and maintain education that involves:

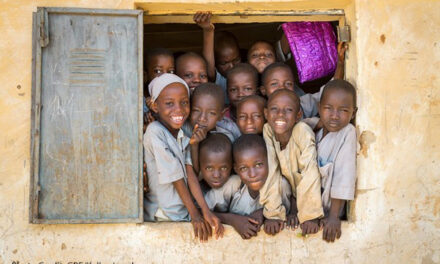

- Equitable worldwide access, with similar opportunities and levels of outcomes across all social and geographical settings from rich Western suburbs to remote impoverished ‘Third World’ villages.

- Appropriateness to evolving global, national and local society and to the emerging duality – virtual and tangible – of contemporary consciousness.

- Appropriateness to all kinds of people, and their interests, capacities and aspirations within their society – lifelong – and geared less to the world of work than to their wider interests and imaginations.

- Affordability – to individuals and their families, to educational institutions, and to governments – in terms of costs, time, resources and commitment.

Clearly, we are talking of a massive project, exceeding for instance space exploration in terms of aspiration and potential for good, and this cannot be the responsibility of any one government. Certainly all nations should participate through their educational thinkers, civil societies, businesses, teachers and learners as well as their political leaders. Multinational companies, conglomerates, think tanks and billionaire gurus cannot be prevented from contributing but must be carefully kept in check. UNESCO should surely take the lead as is justified not only by its formal role but also by its contributions to date. But let it be recognised that we are now talking about moving towards a global solution and, hopefully, what we – in happy participation with AI – can achieve in the education sector, may be replicated in, for example, health, food security, information, entertainment and elsewhere.

Gatherings where participants exchange information and approaches, fears and ideas are enjoyable and, in a marginal sort of way, positive. But here we have, for the first time in human history, a genuine opportunity to define and establish a universally-available yet individually-bespoke educational system apposite to these exciting, terrifying, wondrous times. Let setting in motion that transition become the bases of forthcoming events: I shall book my place at once.