This blog was written by Vongai Nyahunzvi, Chief Network Officer at Teach For All, a global network of independent organizations working in 61 countries to develop collective leadership to ensure all children can fulfil their potential. It was originally published on the Diplomatic Courier on 10 March 2023.

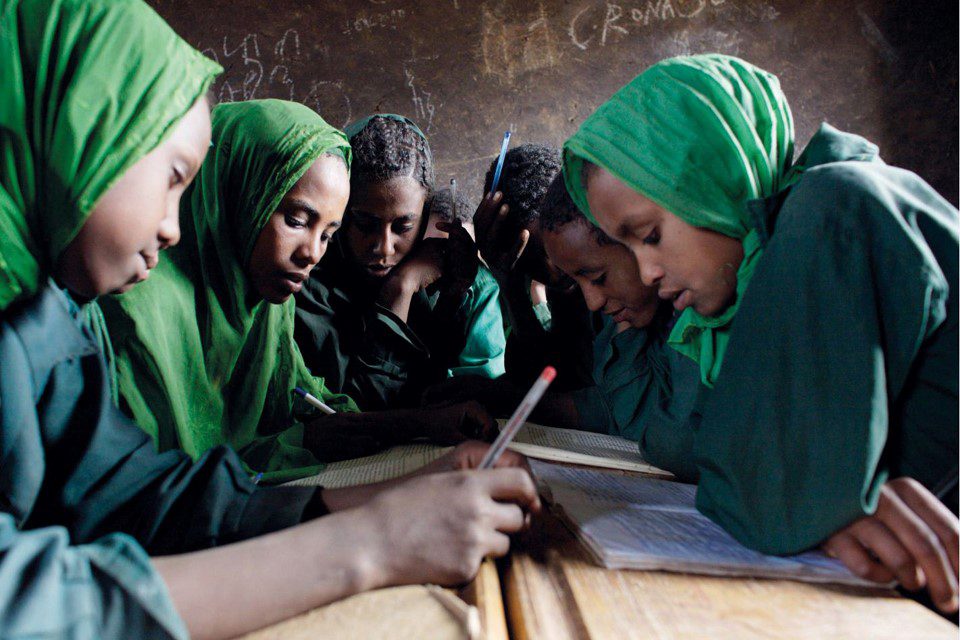

The international development sector is finally getting on board with the need for localization in their work, and there is growing global recognition that meeting the needs of girls and women in the Global South requires a fundamental shift in the humanitarian system. While we have seen positive steps in terms of good commitments, targets, and guidance to better support girls and women in humanitarian aid contexts, ensuring girls and women have a place at the table where these commitments are made is still the exception, rather than the norm.

Although there are differing views on what exactly counts as “local” when it comes to localization, at the heart of the concept is the idea of ownership. In other words, those who are most affected by a situation take ownership and are central in leading the process of devising solutions that address the challenges they are experiencing. Women are the backbone of local economies across communities in the Global South, managing household budgets, and driving food production and local enterprise. In order for any localization drive to be successful, women have to be at the center of its focus.

This is currently far from the case. Strategies for localization are too often being generated in boardrooms and headquarters where women are not sufficiently represented. Globally, women are on the front line of local development efforts, yet they occupy a minority of senior executive roles and board seats—a ratio which is likely even more unbalanced in the Global South. The disparity in the global health sector is indicative of a challenge faced by the whole development sector. This paints a picture of an ailment being treated without the patient being present. When it comes to localization, how can we claim to be bringing solutions closer to the people without the people who are really doing the work being part of the decision-making process?

A conversation with a colleague who leads an organization focused on the education of girls is illustrative of the broader issue. She shared how in the early 2000s, the duty taxes being imposed on sanitary pads in one African country had a significant adverse impact on girls, who had to walk long distances to school and were unable to attend school during their menstrual cycle. Her organization rallied global actors to get the duties removed, only to later learn from a female community member that this particular issue was not their primary concern—the community’s major concern was avoiding starvation, not sanitary issues. The colleague thought she was solving a problem and removing a barrier, but because she didn’t consult with the community first, she missed the opportunity to work on what the women in the community really needed and wanted.

Thankfully, a growing movement of locally rooted agencies are empowering women to take on leadership roles across the Global South. Their work is shifting the way communities perceive women’s leadership, and it is providing opportunities for women to challenge traditional power dynamics.

Hindou Ouramu Ibrahim is a Chadian activist who is improving indigenous people’s access to basic needs and helping to prevent resources-based conflicts in one of the poorest and most vulnerable regions of the world. She has through her organization—Association for Indigenous Women and Peoples of Chad—been able to lean on her experience living in an indigenous community to design and lead projects that are changing the narrative for her community and giving more girls an example to look up to in aspiring to lead better lives themselves in a society where girls face significant barriers to success.

Fresta Karim, who was born and raised in a refugee camp in Afghanistan is working to improve access to education for young children in Kabul through her initiative of mobile children’s libraries. Despite the volatility and challenges faced by women in Afghanistan, she has continued to advocate for the needs of the most marginalized. Hindou Ouramu Ibrahim and Fresta Karim are examples of women leading the way in showing what is possible if local women are empowered to lead local transformation efforts.

Women and girls must be better included in localization efforts than has been the case to date. International NGOs, multilateral donors, and philanthropists wanting to see equitable localization processes should explicitly seek out and fund local organizations in the Global South which are led by women, have women on their boards, and whose strategies are informed by local women. Ultimately, efforts to put decisions in the hands of local people will only succeed if equity and inclusion is at the heart of the localization drive—which means women must be at the center.