This blog was written by Madeeha Ansari, Cities for Children Founder, and Joy Okwuonu, Programme and Communications Officer.

In this blog post, we will consider the impact and implications of our Partners in Learning programme, specifically, in regard to Socio-emotional Learning (SEL) and development.

In April 2020, schools in Pakistan were closed indefinitely to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. This pattern of school closures caused huge concerns about global learning losses: it was estimated that 1.6 billion learners in about 190 countries would be affected. With school closures came increased social isolation. As a result, quick action was necessary to ensure that children’s connection to learning was maintained. This was coupled with a focus on reducing the pandemic’s mental health and wellbeing implications.

Street-connected children were particularly vulnerable to the social and economic shocks of COVID-19 and pandemic-related lockdowns. Many of the education and protection services the children accessed closed down indefinitely and it was hard for them to follow the guidelines to “stay home.” Moreover, the longer they stayed out of school, the harder it was for them to return to education.

The Seekho Sikhao Saathi (SSS) or “Partners in Learning” Programme

Seekho Sikhao Saathi (SSS) – or “Partners in Learning” – was our response to school closures during COVID-19, to support street-connected children served by the Pehli Kiran Schools. The initial pilot of the programme was designed to maintain that crucial bridge to keep children engaged in learning during a period of uncertainty.

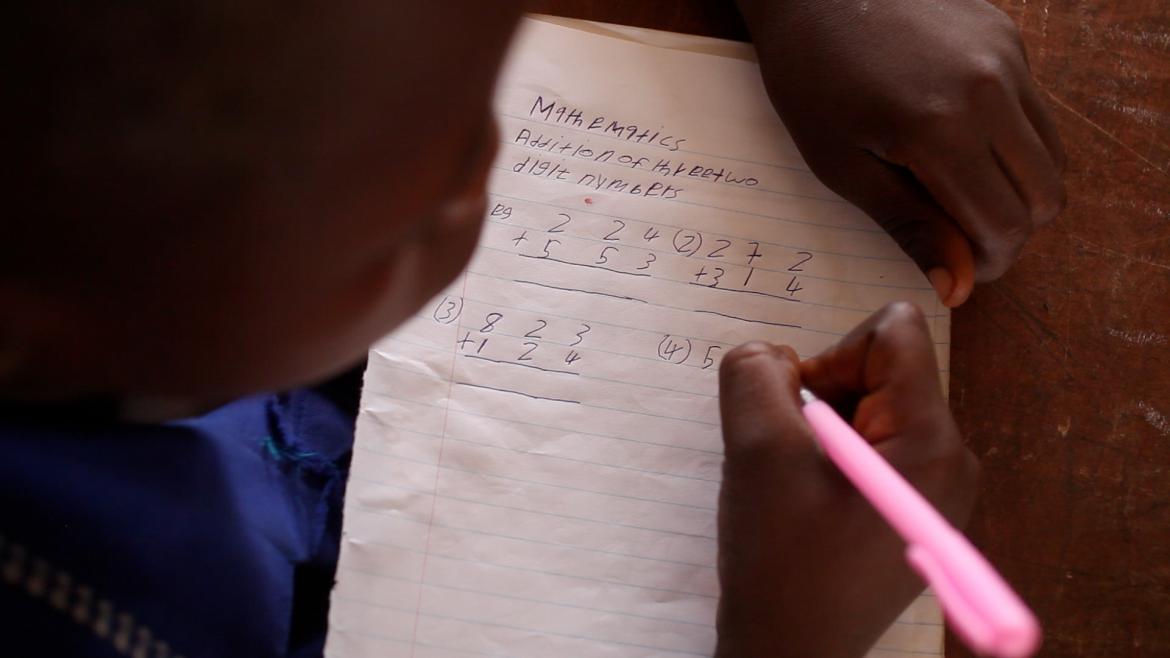

Based on a child-to-child model, we trained older children (Baray Saathi/Big Partners) aged 10-14 years, to deliver playful early learning sessions for pre-school aged children (Chotay Saathi/Little Partners) within their communities, in safe ways, during and after the COVID-19 school closures. Sessions were a combination of adapted content from the Child to Child Getting Ready for School programme; additional play-based learning sessions created by Cities for Children, and some innovation on the part of teachers and Big Partners.

Initially, sessions were designed for one quarter – and until schools opened, 14 sessions were delivered over a 7-week period, kicking off in July 2020. Later, the programme was extended with content being co-created by teachers, to recover from learning losses when schools reopened.

Although it started as an emergency response to the closing of schools, we have now implemented the programme in a range of contexts, from non-formal schools in urban settlements to a Malala Fund school in a remote mountain region. With each iteration, we have refined and added to the content, and it has evolved into a holistic programme which not only works to improve the core foundational skills of the Little Partners but also greatly impact the social emotional learning (SEL) of the Big Partners.

Why does SEL matter?

The importance of developed SEL programmes is increasingly becoming recognised as a priority for educators. Developing emotion skills ensures children learn to understand how they are feeling and find tools to manage their emotions. This is vital for children to develop happy, fulfilled lives. A strong SEL programme that combines these skills enables children to build resilience and, according to Cities and Children, keep “hoping and coping in difficult circumstances.”

Improving socio-emotional skills is strongly associated with better educational outcomes and better socio-emotional skills, which translate into improved school behaviour and also economic benefits. An improved approach to and perception of learning can motivate children at risk of dropping out, to stay in school.

From this, therefore, it seems that SEL is instrumental in supporting children to manage complex situations, make positive life choices and develop well-rounded, happy, healthy and resilient lives.

What impact has the programme had?

Through this SSS programme, we have reached over 1,700 children in Pakistan. The programme is currently being piloted with children from refugee and at-risk communities in the UK.

Capturing SEL has increasingly become a pressing concern in the global discourse now. Our own approach and evaluation framework has evolved over various iterations, moving from a more general clustering of children’s responses under the 5 CASEL domains to a more specific emphasis on the key areas of programme impact.

While our body mapping exercises yield open-ended responses, the following themes emerged as the most significant SEL indicators to track for the future:

- Developing a positive self-image: 34 of 69 (49%) Body Maps reported a positive change in self-image.

- Learning to communicate [relationship skills]: 31 of 69 (45%) Body Maps reported Baray Saathi communicating with more confidence and/or kindness.

- Displaying self-control and non-violent conflict resolution [self-management]: 20 of 69 (29%) Body Maps showed Baray Saathi controlling their anger and utilising non-violent conflict resolution.

- Developing empathy and care [Social Awareness]: 17 of 69 (25%) Body Maps showed Baray Saathi increased their care of the community and building of relationship management skills.

In addition, we’ve seen the programme to have a positive impact on the following:

- Impact on the Baray Saathi’s sense of agency: This was effectively seen in the creative ways that they problem-solved issues that arose in the classroom.

- Creative teaching: The Baray Saathi were encouraged to make the curriculum their own by developing innovative and creative activities for the Chotay Saathi. For example, one Bara Saathi introduced the idea of ‘learning with sound.’ They helped the Chotay Saathi learn the names of various fruits by cutting and pasting images of those fruits.

“In Big Partners, I have seen incredible amounts of courage, resilience, and a boundless vision for leadership. It has been an incredible experience to witness their courage and their rediscovery of childhood, of joy, and of love.”

(Feedback from Sahar Gul, Programmes Officer within Cities for Children Pakistan).

- Motivation and Learning: Learning was no longer seen as a chore, but instead, involved the hearts, minds, and hands of the Baray Saathi. Many students noted that they had a newfound desire to learn because of the joy they felt at school and in the learning process itself.

“My heart wanted to play all the time, now my heart wants to study.”

(Feedback from one of the child participants).

Motivation to continue learning is especially important for girls as in Pakistan – only 13% of girls reach Grade 9 (Malala Fund). In our analysis, 50% of total counts expressing a motivation to stay in school were female students.

- Goal setting: In all, the programme prompted Baray Saathi to look into their future and set goals for themselves broadly.

“I used to think why should I study, how will studies help me, now I think I should focus on studies to become something.”

(Feedback from one of the child participants).

- Academic skills: Baray Saathi shared that they developed academic aspirations after SSS and their determination to make responsible academic decisions to achieve them.

“I wanted to become a teacher, but I wasn’t working hard for it, now I am working hard to become a teacher.”

(Feedback from one of the child participants).

Learnings from the Partners in Learning programme

Giving children freedom to lead. It is important for children to be given the freedom to be creative in the classroom or informal learning environment. Over the course of the programme, our team found that it takes time for teachers to let go to facilitate the child-led sessions. Enabling peer learning is integral to this process. Peer learning among Baray Saathi makes a huge difference not only in how the programme is delivered but also in the general attitude of Baray Saathi.

Adult support for Big Partners. Supplementing this child-led, peer learning with an enhanced coaching element can be beneficial. Baray Saathi do incredibly well when provided with coaching support through Cities for Children personnel – this was shown to not only help them reflect and do better vis a vis their sessions but to also understand deeply the role that they are playing in the Chotay Saathi’s lives. This coaching element, if pursued consistently, can be an element of leadership development for Baray Saathi which can develop their sense of agency and responsibility beyond the classroom and school.

Teacher and admin buy-in are incredibly important: The weekly in-person touchpoint of the Baray Saathi with teachers was absolutely crucial for the quality of the programme, to go over and practice the session plans, troubleshoot and fill out weekly reflection records. We need to engage teachers and provide them with sufficient support to deliver. However, teachers in schools have huge capacity issues and may not be able to offer Baray Saathi more than a revision of the lesson plan. During the course of the programme, Baray Saathi sometimes needed a bit more technical support, particularly in science sessions.

“In my work with teachers, I have been awe-inspired by their seemingly unending capacity to work for children. Despite being heavily burdened by work, given that they are most often working extremely under-capacitated, they have risen to the occasion for the sole purpose of supporting the children they are teaching.”

(Feedback from Sahar Gul, Programmes Officer within Cities for Children Pakistan).

The SSS programme has had a number of impacts on the younger and older children or ‘Big Partners’, notably their socio-emotional learning and development. We intend to use the above findings to strengthen the SEL components of the SSS programme and its wider community impacts.

————————————

You can find out more about our work and the Partners in Learning Programme by visiting our website, or contacting us. Follow us on Twitter @Cities_Children to find out more.

We are grateful for insights provided in the internal reports by programme staff and evaluation consultants, including Sahar Gul and Minha Khan.

This is a very impressive contextualisation of Child to Child’s original model of Getting Ready for School (not always aptly named!).

This model has stood the test of time, having been piloted by UNICEF n 6 countries over a decade ago.

In today’s world, where children need all the help they can get with early learning in post-COVID, conflict and under-resourced or remote situations, Child to Child and Cities for Children believe this model can help us reach the SDG. It is also being utilised in Uganda and elsewhere. If we wait until a system can reach these children, they will lose out forever.