This blog is written by Dr Ha Yeon Kim, Senior Research Scientist at NYU-Global TIES in Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development. Working in close collaboration with local and global stakeholders, Ha Yeon is committed to improving academic and social-emotional learning and well-being for children affected by crisis and adversity around the world.

The recent earthquakes in Turkey and Syria hit an already war-torn region and populations in the Middle East. They have left lasting psychological and physical trauma for 8.8 million affected people in Northern Syria alone–a region where 4.1 million people already depend on humanitarian assistance. While immediate emergency responses are essential, once the initial crises pass, children impacted by conflict and crises still need to grow up and learn, coping with painful memories and unpredictable and often hostile environments. They deserve and need support that can help them to navigate the adversities on their own.

A Syrian refugee girl opens a door to her tent classroom, welcoming in the researchers, Lebanon informal settlement.

Unfortunately, the disruptions in the aftermath of crises can exacerbate the emotional and psychological toll on children, affecting their physical and emotional well-being, learning and development over the long term.

One potential solution that has gained traction is school-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programmes that focus on equipping children with skills needed to cope with stress, trauma and uncertainty, rather than treating the symptoms. Despite their importance and rising popularity however, there is limited evidence available on how SEL programmes work with children with more severe exposure to conflict and violence. For practitioners and researchers in this field, it is critical not only to understand whether these programmes work but also to ensure that they do not cause harm to children, particularly those who have experienced significant trauma and adversity. When it comes to directly intervening in children’s social and emotional skills and functioning, with a population that is likely to have been deeply emotionally affected, no amount of caution can be too much.

A newly published study from Lebanon, conducted by researchers from Global TIES for Children at New York University and the International Rescue Committee (IRC), provides promising evidence that such SEL programmes can improve children’s social and emotional skills at scale without causing more harm to vulnerable children. We saw in our data that Syrian refugee children who had experienced high levels of conflict, especially war violence and bullying, had poorer mental health as well as poorer cognitive and emotional regulation skills. In the hope of providing support for social and emotional needs for all Syrian refugee children at scale, IRC implemented a newly developed SEL programme called the Five-Component SEL (5CSEL) curriculum.

5CSEL is designed to improve children’s cognitive and emotional regulation, positive social skills, conflict resolution skills, and perseverance in non-formal remedial classroom settings. In our evaluation, the 5CSEL curriculum showed promising signs of improving some of the targeted social and emotional skills for Syrian refugee children, including their ability to regulate their own emotions and behaviours in learning contexts. These positive signs suggest that SEL programmes like 5CSEL—with improved design and implementation—can promote refugee children’s SEL skills. However, the overall evidence of positive impact was inconclusive, which calls for further revision of the programme design and implementation. It also suggests the need for targeted investment in research that can inform how to improve SEL programming, like 5CSEL, to better cater to the children’s needs, culture and contexts.

Importantly, the study also found no evidence of potential harm for refugee children who experienced severe exposure to conflict. This provides initial evidence supporting the argument that universal SEL programming like 5CSEL can be used widely for children affected by conflict and crisis at scale, without causing harm. Given the extreme vulnerability of children we work with, it is important to vigilantly monitor, evaluate and document how SEL programmes work for children with different experiences and backgrounds before we can comfortably say SEL programming is safe and effective for all children.

A group of Syrian children in IRC’s remedial tutoring programme working together with their female teacher to learn how to write an Arabic letter, Lebanon informal settlement.

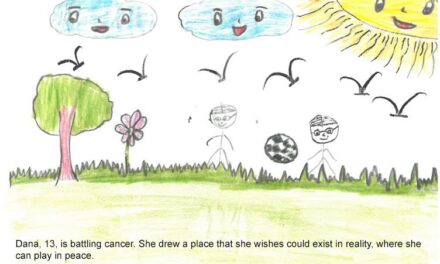

Over 222 million school-aged children are affected by armed conflicts and crises globally as of 2022. This number is expected to continue to rise due to ongoing crises and disasters. In the reality of the compounding trauma and protracted crises that so many children are living through, we need sustainable and scalable solutions to support children’s long-term learning and well-being, beyond emergency responses. SEL programmes show promise in this regard, but evidence on both their effectiveness and safety is still limited. To transform this burgeoning field into successful and sustainable solutions, we need substantial investment in designing, implementing and researching SEL programmes. This investment will help build systematic and evidence-based approaches to SEL that can safely support children’s learning development, and well-being, without causing any further harm. As we work to rebuild communities devastated by crises, we must prioritise the emotional and psychological needs of affected children for a sustainable future. One way to do so is to invest in the development of and research on SEL programmes to improve their effectiveness and safety. It is essential to learn how to help safely before trying out these programmes with children, without knowing their impact.

| Main image description: A Syrian refugee boy seated in a dimly-lit tent waiting his turn for social and emotional assessment, Lebanon. |