This article was written by Abdirizak Haybe Ali, an education columnist based in Jigjiga, Somali Region of Ethiopia.

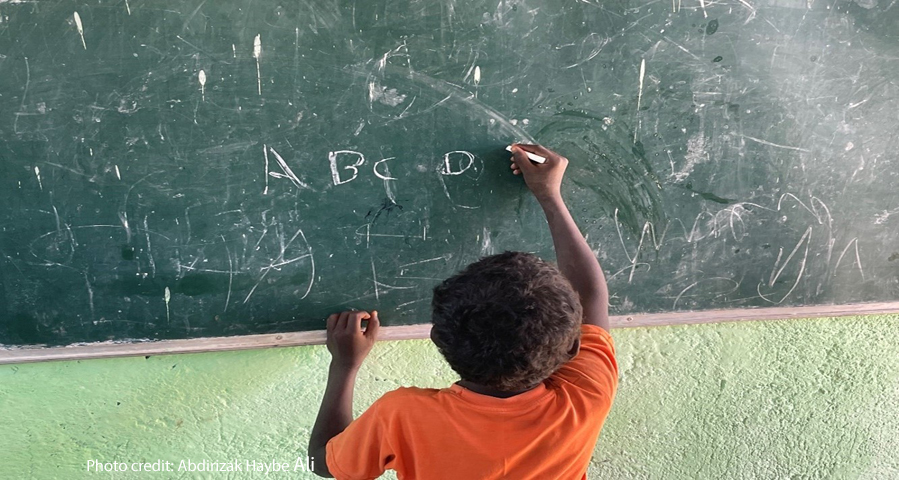

Despite all of the known benefits of education, the learning crisis persists across the world. In Ethiopia, lower primary in particular is extremely stunted by poor quality learning systems. Parents are upset by their children’s lack of basic literacy and numeracy skills, and blame the government. They claim that the Regional Education Bureau, along with the Ministry of Education, is mandated to deliver inclusive quality education to their children. The country has made considerable gains in improving access to education over the last couple of decades, yet the returns from investment in education are hindered by low levels of education quality and increases in frequent climate-induced crises. Despite quality of education being a key indicator for a country’s progress, the Somali Region particularly demonstrates heartbreaking results. This blog aims to show the status of education in the region and suggests possible solutions for addressing the challenges.

According to Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Education Annual Abstract data of 2021, the country has displayed tremendous strides, yet needs to future-proof any achievements in progress. Yet more needs to be done – especially to encourage primary education to flourish, as this is the level that engages with the highest number of learners compared to any other.

Early childhood: The Ministry of Education developed a national Early Childhood Care & Development (ECCE) policy framework in 2010. ECCE plays a crucial role in preparing children for primary education, and has the potential to increase levels of enrolment and reduce incidences of drop-out and grade repetition, particularly for girls. The policy aims to improve children’s growth and development through improving ECCE service delivery. The Ministry of Education formulated three different modalities for ECCE delivery:

- Kindergarten (3 years): Predominantly operated by non-governmental organisations, communities, private institutions, and faith-based organisations. Of the three modalities, children who attend kindergarten are most likely to be sufficiently prepared for primary.

- Child to Child (1 year): Older children play with younger siblings or other children in their community, supervised by qualified teachers, to teach basic skills such as counting, differentiating colours, and identifying letters, before joining primary school.

- ‘O’ Class (1 year): Reception class based in government primary schools for children aged 6, before starting formal schooling at age 7.

At national level, 36.7% of children are enrolled in pre-primary classes, while in the Somali Region this is just 3.2%. This is exceptionally low, despite ECCE being the entry gate to education. The region is desperately lagging behind, with minimal investment at this level of education.

Gross enrolment rate: Primary education acts as a benchmark for other proceeding levels of education and therefore receives the largest share of government education spending in Ethiopia. The national gross enrolment rate for primary education is 102.6% (Grades 1-6) and 70.0% for middle school (Grades 7-8). In contrast, in the Somali Region, the gross enrolment rate for primary is 100% (Grades 1-6 ) and 37.5% for middle school (Grade 7-8). This indicates that many students are not progressing from primary to middle school – they are either repeating grades or dropping out completely. This signifies a low transition rate between the two levels and it is important to assess factors contributing to this.

Net enrolment ratio: The national net enrolment ratio is 86.4%, while in the Somali Region this is 69.1%. This measures students’ enrolment for those who are in the official age group for their given level of education, from the ages of 7 to 14 years old, who are enrolled in primary and middle education, including alternative basic education. There is a wide regional variation, with Afar and Somali having a much lower net enrolment rate than other regions. This low figure may be driven by various aspects, including the recurrent drought forcing pastoralist children to migrate from their area of origin, disrupting their learning.

In addition, there is a widening gap between the two levels of primary education. In the Somali Region, the net enrolment ratio is 73.9% at primary level (Grades 1-6), yet only 14.3% at middle level (Grades 7-8). Children aged 13-14 are not progressing in the education system due to unfavourable learning environments or persistent socio-economic crises at the household level, because families cannot afford the support their children need, including school uniform, school materials and other items.

Gender parity index: The national gender parity index (measuring equity between girls and boys) is currently 0.90 for primary and 0.94 for middle, or 0.76 and 0.75 respectively for the Somali Region. The region is lagging behind and it is paramount to set up relevant programmes to support girls to enrol in learning opportunities and participate. There is still a preference of choosing boys to send to school and girls are largely kept at home for household chores. These programmes need to involve sensitising the family to be aware of the value of girls’ education and creating environments that accommodate girls’ needs and support.

Pupil-teacher ratio: A lower pupil-teacher ratio indicates better opportunities for contact between the teacher and pupils, and this improves the teaching-learning process as teachers have ample time to support children in the classroom. The minimum standard set for this ratio is 50 at primary and middle schools and 40 at secondary level. The national pupil-teacher ratio in Ethiopia for the year 2021 was 34.8 for Grades 1-8. This is highest in Somali (61.2) – highlighting overcrowding and class congestion in the region. Although there has been a significant improvement compared to some years back, it is still important to aim for the national minimum standard and construct additional learning facilities.

Textbook to pupil ratio: Nationally, the textbook to pupil ratio for primary is 3.5, and 6.4 for middle school. The ratio is high in Harari, Addis Ababa and Amhara at primary and middle level and the lowest in the Somali Region. This textbook crisis has negative impacts on children’s education.

School facilities: Appropriate facilities play a substantial role in creating a decent learning environment. Electricity, access to multimedia teaching, a library, laboratory and pedagogical centres, all provide considerable inputs to the improvement of an education system. Despite this, education facilities at national level are only 30.4% in primary and middle levels, which is below the standard; for the Somali Region this is even lower and has not been progressing, causing serious repercussions on children’s learning opportunities.

School WASH facilities: Across the country, it is common for schools not to have any water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities – but a wide variation exists between regions. Access to a water supply at national level is 40% in primary and middle schools, with only 76% of these being functional. The Somali Region has the lowest access rate of 21.5%, with wide variations between zones and woredas of the region. The lack of these basic facilities is critically undermining girls’ participation and enrolment.

Secondary school enrolment: Secondary education is the entry gate to higher levels of education. At national level, enrolment has expanded rapidly in the last 20 years, increasing with an average annual growth rate of 8.5% in the last 5 consecutive years, but not evenly across all regions. The national gross enrolment rate for secondary education is 42.1%. The transition from primary to secondary education is low with persistence of regional disparity. The Somali Region gross enrolment ratio for secondary education is 25.7%. In 2021, despite the region having 397,764 school-aged children, only 102,341 were enrolled. This is just a quarter of the possible population.

Nationally, the net enrolment ratio for Grades 9-12 is 29.5%, a very slight increment from the previous year. For the Somali Region, this is 14.7%, which is insignificant when compared to other regions. Multiple reasons are undermining the secondary net enrolment ratio of the region, including the lack of investment in school infrastructure, incompetence of teachers, low pupil-teacher ratios, lack of textbooks and lack of adequate WASH facilities.

In 2022, leaving certificate results were discouraging and heartbreaking across Ethiopia. Nationally, only 3.3% of children scored above 50% (the prerequisite mark to join university), while in the Somali Region, only 0.7% of children scored above 50%.

Possible solutions: The extent of the challenges are enormous for the Somali Region. These recommendations provide some possible solutions for strengthening the region’s education system.

- Investing in the education system and allocating a robust budget for bridging widening education gaps will help address the burden of poor quality education. The regional government should provide better financing to the education sector, to the tune of allocating more than 15% of the region’s total budget. There are also compounding needs in other sectors, yet prioritising education is important and will have long-term positive impacts on the socio-economic development of the region through producing competent, skillful and knowledgeable citizens who can contribute to the country’s and region’s developmental endeavours.

- Building education resilience is paramount since the region is prone to climate-induced hazards (mainly drought). A sturdy system needs to be in place to avert external threats and minimize the risk of children dropping out – particularly through financing for education in emergencies and allocated funds from the presidential office and Regional Education Bureau.

- Building synergies with other developmental bureaus is crucial, such as the Health Bureau, Water Resource Development Bureau, Regional Disaster Risk Management Bureau and any other relevant regional bureaus. Joint planning and an integrated sector response is crucial, for example a one-WASH project, the Productive Safety Net Programme and the health and nutrition response from the Health Bureau.

- A school feeding programme should be considered as the top priority of the Education Bureau’s plan; in particular, targeting the many schools positioned in the region’s peripheral and hard-to-reach areas as these are overwhelmed by incessant climate-related disasters.

- More investment is needed in inputs which improve quality, like a library, laboratory, pedagogical centres, capacity building of teachers and certifying their profession.

- Strong accountability systems need to be set up for the Regional Education Bureau in order to supervise and assess school performance to ensure that lower primary grade children are mastering the foundational skills and have proficiency level in reading and writing.

- Parents’ engagement, follow-up and support to their children’s education is one of pillars of improving children’s learning outcomes. Learning through just classroom lessons is not enough; learning also requires continuous support from parents/caregivers at home.

- Community sensitisation on the value of education, as well as private sector involvement, are both important for the support of the education sector.