This blog was written by Siddharth Pillai, Education Programmes Advisor for Street Child in Afghanistan. With thanks to Ashan Abeywardena, Kshitiz Basnet, Sarfaraz Sahibzada, Izatullah Mangal, Hamidullah Ahmadzai, Saadatullah Babakarkhil and other members of the South Asian Assessment Alliance for their support and contribution to this article.

Since 15 September 2023, there has been a significant increase in the number of people returning to Afghanistan, primarily through the Torkham and Spin Boldak border crossings. The announcement on 3 October 2023 by Pakistan to repatriate over a million foreigners, mainly Afghans without valid documents, led to a consistent rise in returnees crossing the border points with the number of recorded returnees crossing at 500,000.

Among the returnees, the most vulnerable are children, constituting 24% under the age of 5 and a significant 60% aged 17 or younger. Based on the border consortium data obtained from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the following are the top five provinces where the maximum number of children aged 6-17, intend to return.

| Province | Number of returnee children aged 6 to 17 intending to return |

| Nangarhar | 51,382 |

| Kandahar | 30,079 |

| Kabul | 17,648 |

| Kunduz | 14,275 |

| Kunar | 13,499 |

Status of education among Afghan returnee children

To understand the educational needs and learning levels of returnee children, Street Child and Keenly Humanitarian Assistance for New Afghanistan (KHANA)-led South Asian Assessment Alliance conducted a rapid assessment in Torkham in coordination with Agency for Rehabilitation and Energy Conservation in Afghanistan (AREA) and Liberty, Equality, Fraternity Afghanistan Organization (LEFAO) who are members of South Asian Assessment Alliance, from 19-21 December 2023. A total of 46 household representatives participated in the ASER-type assessment, shedding light on the foundational literacy and numeracy competencies of 105 returnee children which included 21 girls and 84 boys. South Asian Assessment Alliance ensured that all children who returned from Pakistan during these few days of December were part of this assessment.

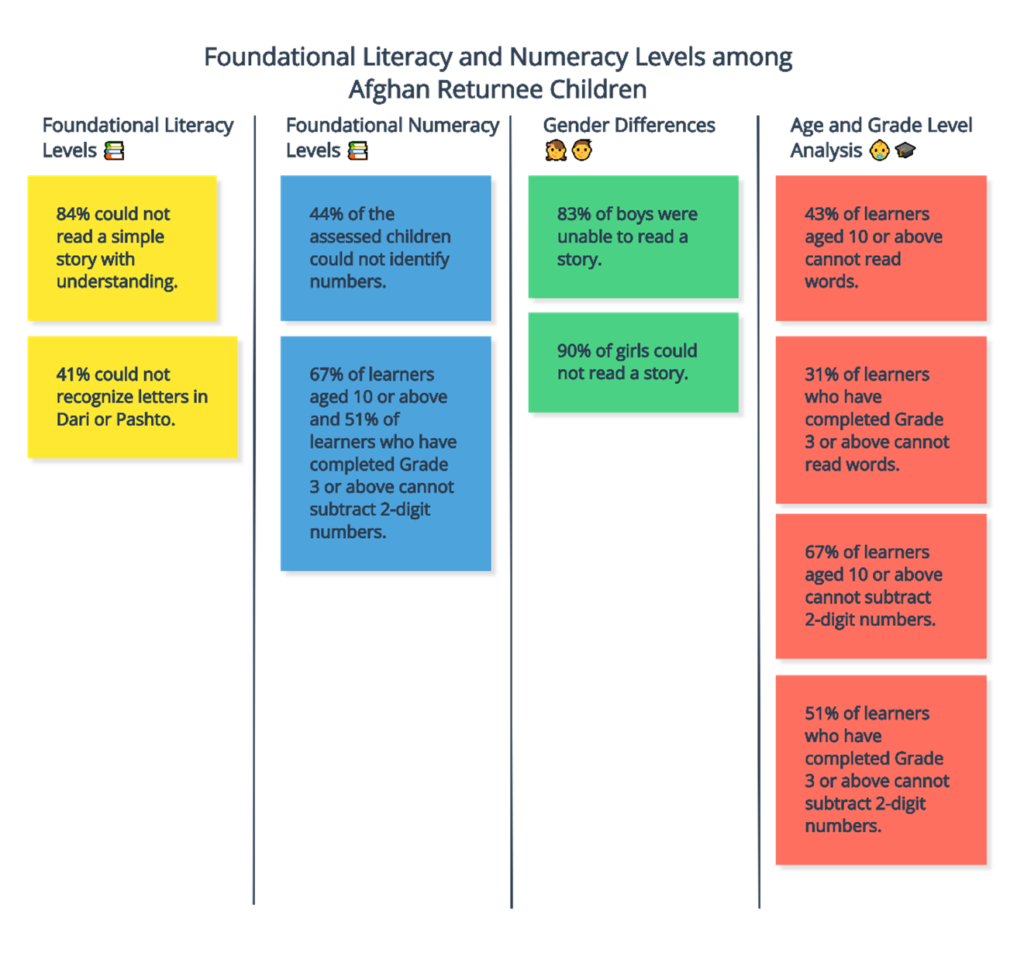

In terms of foundational literacy, while most of the assessed children could speak Pashto/Dari, 84% could not read a simple story with understanding and 41% could not recognise letters in Dari or Pashto. While 83% of boys were unable to read a story, 90% of girls could not do so. 43% of learners aged 10 or above and 31% of learners who have completed Grade 3 or above cannot read words.

In terms of foundational numeracy, 44% of the assessed children, could not identify numbers. A substantial proportion of the learners who are aged 10 or above or completed Grade 3 or above cannot subtract 2-digit numbers. 67% of learners aged 10 or above and 51% of learners who have completed Grade 3 or above cannot subtract 2-digit numbers.

The findings are summarised in the infographic below:

The assessment also uncovered a myriad of challenges hindering the education of returnee children. From bureaucratic hurdles in school enrolment procedures to linguistic barriers and financial constraints, returnee households face or foresee multifaceted challenges in accessing quality education for their children. More than 80% of returnee children surveyed, studied in Urdu or English medium schools which highlights the linguistic barrier the learners are going to face as they try to integrate into Pashto/Dari medium schools. To address these challenges and pave the way for inclusive and equitable education, a comprehensive approach is imperative.

Recommendations

- Remedial education and bridge programmes: As educators aim to integrate returnee children into the education system of Afghanistan, it is imperative to understand and respond to the foundational learning needs of returnee children. The above-mentioned findings refer to the need to have remedial education and bridge programmes as an integral part of the education in emergency response. Bridge programmes are essential for returnee children to learn to read Dari and Pashto with understanding as most of them previously studied in Urdu medium schools in Pakistan. In the absence of such a bridge programme, these children would lag further behind and drop off at higher grades where they need to read to learn from textbooks.

- Strengthening public schools and community-based education centres: Establishing community-based education (CBE) centres and enhancing the capacity of public schools are vital steps towards ensuring access to quality education for returnee children. Previous studies conducted in high returnee areas of Nangarhar show that 37% of the returnee children are out of school. The proportion of children who are out of school increases to 50% in areas that are more than 3 km away from the school. During the study, the community cited the lack of school supplies, overcrowding of classrooms, lack of transport facilities and absence of catch-up classes as some of the problems which need to be solved as a priority. The low access and overcrowding of secondary schools in high returnee areas were also cited as a major problem as children aged 15-17 form a major share (30.7%) of school-aged children.

- Psychosocial support (PSS): PSS is highly recommended so that they not only positively cope with the stress associated with displacement but also mitigate the risk that emanates from the classroom or school. According to the 2019 Survey of Afghan Returnees, more than half of returnees reported feeling discriminated against because of their language and manner of speaking (56.8%). Those who lived in Nangarhar and Kandahar were more likely to report discrimination based on language (82.1% and 65.8%, respectively) when compared to those living in Balkh (54.1%) and Herat (53.8%). The returnee children from Pakistan who spoke Pakistani Pashtun often struggle to keep up with the rest of the class and hence feel neglected.

- Awareness campaigns and advocacy: Raising awareness among parents about school enrolment procedures and advocating for policy reforms to facilitate the integration of returnee children into the education system are crucial steps toward ensuring equitable access to education for all children in Afghanistan.

As we plan to address the educational needs of returnee children, it is also an opportune moment to bridge the humanitarian-development continuum paving the way for recovery and resilience in education, especially in the high returnee areas of Nangahar and Kandahar. Alongside community-based initiatives in underserved areas, building capacity within public schools to cater to more children and effectively run mental health and phsyco-social support (MHPSS) and bridge/remedial education programmes shall become a rising tide that lifts all boats.