This blog was written by Obiageri Bridget Azubuike, PhD, Education and International Development Researcher.

Foundational literacy and numeracy skills are the pillars on which the rest of a child’s education are built, these skills are indispensable for attaining future skills and educational outcomes. For children who do not acquire the foundational numeracy and literacy skills at basic education levels, continuing education becomes increasingly challenging. Consequently, they face limited opportunities to pursue higher education, and their potential for developing essential employability skills are significantly reduced. According to the World Bank, by the end of basic education, a child who is unable to read will struggle to catch up because as students progress in the education system, the lack of basic skills will act as a hindrance to the development of other skills and many schools do not offer struggling students room to catch up during the school year.

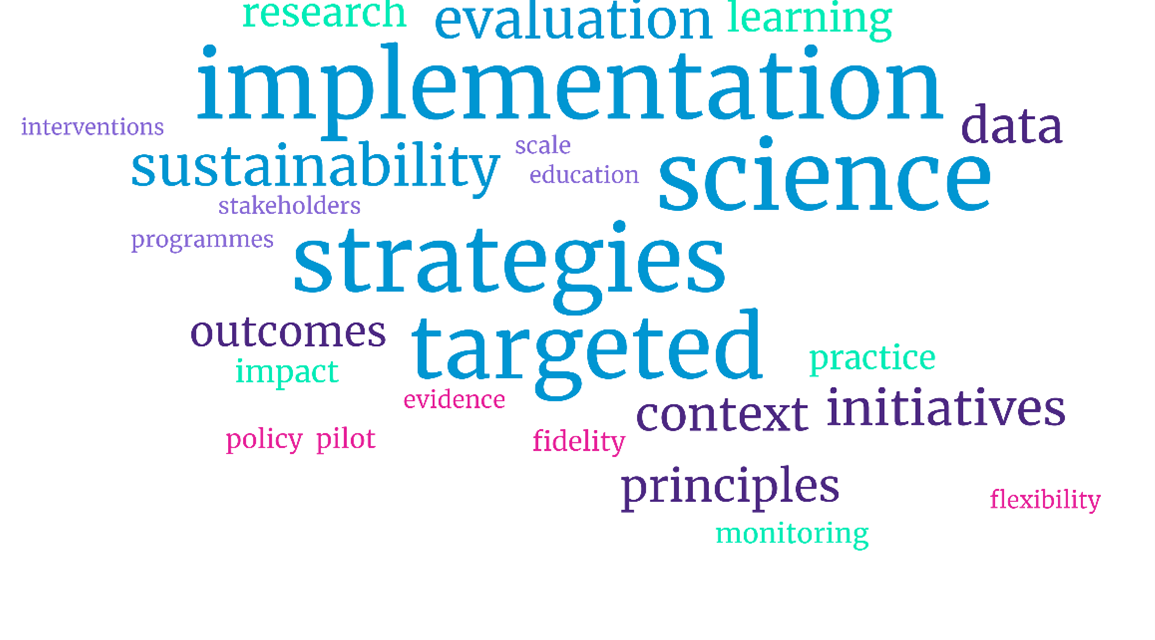

Given the pivotal role of foundational literacy and numeracy skills in education, policies aimed at their development emerge as crucial focal points for scaling up effective interventions. The transition from pilot programmes to policy implementation underscores the transformative potential of scaling up initiatives. This article explores the application of implementation science principles to scale up foundational learning interventions, emphasising the importance of evidence-based practices in shaping educational policy and practice.

Implementation science is a term which has come mainly from the health sciences and has been defined as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” (p. 1). Implementation science examines contextuality and feasibility in the uptake of interventions, implementation fidelity and sustainability of the practice. The field of implementation science for education interventions is still new, and there is a growing body of literature on the subject. However, some of these studies do not link their work directly to the term but provide evidence of implementation science in action.

An in-depth example of implementation science in India discusses how to move from concept to scalable policies using the application of Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL). TARL addresses the deficits in students’ basic literacy and numeracy skills by dividing students into groups based on their individual learning needs rather than age or grade, emphasising the acquisition of foundational skills alongside the curriculum, and conducting regular assessments to gauge student performance rather than relying solely on end-of-year exams. TaRL scaled successfully from two slum cities to several states across India, using a simple idea to group children according to their knowledge, i.e. organising children according to their level and matching the teaching to that level. The first attempt to scale TaRL saw the intervention implemented in different versions to identify the version that worked at scale. One of the main challenges of the implementation was getting teachers to not only use the materials to teach but also ensure that the critical component of the model (targeted teaching at the children’s levels) was implemented. In order to overcome the challenge of teachers not fully implementing the programme (implementation infidelity), several strategies were employed and strengthened through extensive process monitoring: Firstly, the government’s explicit endorsement and involvement in the programme were emphasised. Secondly, a dedicated hour within the school day was mandated for the programme, signalling government commitment. Lastly, a structured approach was taken during this hour, reassigning children to achievement-based groups and physically changing classrooms from grade-based to level-based, removing teacher discretion on grouping by levels. These strategies to ensure compliance with the programme saw an increase in students’ mathematics achievement results compared to a previous version without the strategies.

A different multi-country study focused on providing educational interventions to primary school children in India, Kenya, Nepal, Philippines, and Uganda through mobile phones. Findings showed that weekly phone call tutorials, which provided targeted and personalised numeracy instruction, had consistently large and robust effects on learning outcomes across all contexts, with average effects of 0.30-0.35 standard deviation. This study also employed pedagogy similar to TaRL, which targeted students’ learning levels rather than school grades. They report that deploying scalable technology (i.e. mobile phones) and education best practices (e.g. tutoring, one-on-one instruction, frequent assessment, and targeted instruction at the student’s level) were critical for the programme’s success. An important takeaway from the study is that the differences in the effect sizes observed across the different countries came from the progressive improvement in the intervention’s implementation fidelity over successive iterations from country to country. This improvement was measured through detailed monitoring data. Highlighting the importance of monitoring and evaluation in ensuring the effective implementation of interventions.

Learning from the two studies, a critical insight into successfully moving from pilot to policy is the power of implementation fidelity: “Implementation fidelity refers to the degree to which an intervention is implemented, and if it is conducted in accordance with the designers’ intentions” (p. 2). For interventions to be effective, they must be adopted with fidelity, as this ensures the programme’s sustainability. The studies also argue that the critical ingredient needed for the successful scaling of any intervention is maintaining the core components, which are “regarded as essential aspects of the intervention without which the practice or programme will fail to be sustainable or effective” (p. 2). Factors that influence the fidelity of the interventions include the degree of effort required for implementation and the commitment of stakeholders. The TaRL study in India reports that teachers failed to implement the TaRL programme correctly because they did not view it as their core responsibility and felt it required extra time and patience. For the successful implementation of change within an organisation, it is crucial that all individuals feel both committed and confident in their collective ability to change practices.

Several important takeaways become apparent from the literature on scaling interventions and the brief discussion above. For successful scaling of interventions, there needs to be an identification of the “critical” components of the programme and appropriate monitoring and measurement of fidelity data. Without measurement, it is impossible to discern which specific intervention components are crucial for enhancing effectiveness. Lastly, the buy-in and commitment of the custodians of the intervention cannot be overemphasised because, without it, the programmes have little or no room to succeed.

Furthermore, findings from the India study underscore the significance of various factors in the scaling-up process of intervention. Firstly, they emphasise the critical role of collaboration and learning between researchers and practitioners. Secondly, they point out the importance of strategic decisions, such as selecting the appropriate level of randomisation, the right implementer, the suitable geographical area, and the optimal level of involvement by the research team. Lastly, they highlight the essential consideration of context and the necessity for flexibility and fine-tuning. Other key lessons highlighted through the multi-country study are leveraging existing infrastructure (e.g. mobile phones or school infrastructure) and implementing in-demand solutions (e.g. solutions addressing the global learning crisis).

In conclusion, implementation science in the scaling of educational interventions is poised to play an increasingly vital role in education and international development. As global efforts intensify to address challenges such as reducing out-of-school numbers and tackling learning poverty in developing countries, there is a growing need to identify (cost) effective strategies for improving learning at scale. This emphasis on evidence-based practices and integrating research findings into scalable interventions will be crucial in shaping the future of educational initiatives, contributing to more impactful and sustainable outcomes in the pursuit of global education goals. Scaling up foundational learning interventions requires a concerted effort to translate promising practices into widespread impact. By harnessing the principles of implementation science, we can navigate the complexities of scaling and ensure the successful integration of evidence-based interventions into educational policy and practice.