This blog was written by Dr Ruth Naylor, independent consultant.

In a previous blog about refugee education, I concluded that: “since the returns on investments in refugee education are global, investment in the recurrent costs of refugee education should be shared by the global community.” This got me thinking about what a “fair share” of investment in refugee education would look like on a country-by-country basis. So in this blog I present a “straw man” economic model for responsibility sharing in refugee education, and then explain why it would not work in practice.

Firstly, let’s assume a world in which all refugees and asylum seekers are included in national education systems, with the recurrent costs covered by host governments. Then imagine a global investment fund, big enough to cover the recurrent costs of educating all the refugees and asylum seekers in the world. All countries would invest a share in proportion to the size of their economies. Ministries of Education in hosting countries would then receive an annual grant from the fund, based on the number of refugees and asylum seekers hosted. The money could be spent on any element of the education budget, and in any part of the country. The only conditionality would be that refugees and asylum seekers can access education services on the same basis as nationals (I would include a further conditionality on gender equity, but that’s irrelevant to the model).

How big would the fund need to be? The UNHCR and the World Bank estimate that it would cost around $4.85 billion a year to include all refugee students in low- and middle-income countries within national education systems. But their model is based on the current unit costs of host country national education systems. Given that many low-income refugee hosting countries spend less than $50 per primary student per year, it is difficult to argue that this level of investment in education is sufficient. So instead I take the global economy, with a GDP of $100 trillion in 2022, and the globally recommended minimum public investment in education of 4% of GDP. With a global population of 8 billion, that means the world should invest $500 in education per person. The UNHCR estimates that there were 40.7 million refugees and asylum seekers in 2022. Based on these figures, the world should invest $20.35 billion a year in education for refugees and asylum seekers.

If countries were to pay their “fair share” of refugee education costs, the USA, which accounts for over 25% of global GDP, would need to invest $5.2 billion into the global fund. The USA hosts around 390,000 refugees and asylum seekers (less than 1% of the total), so it could claim an annual grant of $195 million. The USA’s net annual payment to the global fund would be $5 billion.

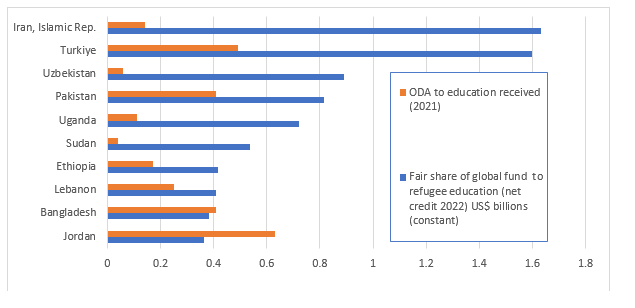

At the other end of the scale, Iran, which accounts for less than 0.4% of global GDP, but hosts over 3.4 million refugees, should invest a share of $79 million, whilst claiming a grant of $1.7 billion, so its net annual credit from the global fund would be $1.6 billion.

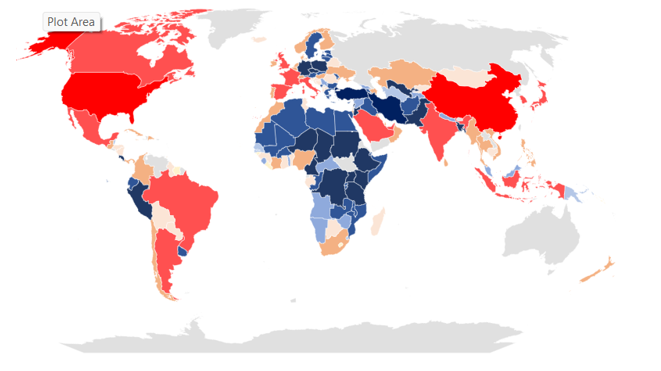

Figure 1 shows which countries would owe the most (in red), and which countries could claim the most (in blue) from a global fund for refugee education, if each country was to invest its fair share in the global costs.

Finding figures for the actual amounts invested by different countries in education of refugees and asylum seekers is very difficult, but we can compare the estimated “fair share” to the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) earmarked to education that has been given and received by different countries. According data published through the OECD Development Assistance Committee Creditor Reporting System, the USA gave $1.3 billion ODA to education in 2021, representing only a quarter of its “fair share” to refugee education. In comparison, Germany gave $3.4 billion ODA to education when its “fair share” of a global fund for refugee education would be a net credit of $0.34 million.

Looking at the total ODA to education received by refugee hosting countries also presents interesting contrasts (see Figure 2). Iran, Sudan and Uzbekistan receive ODA that amounts to less than 10% of their “fair share” of a global investment in refugee education, whereas Jordan receives 170% of its fair share. And therein lies the primary reason why such a fund would never work in practice: geopolitics of aid and international migration.

The other flaw is one of perverse incentives. The fund would incentivise inclusion of refugees in national education systems. But it could also disincentivise host countries from supporting durable solutions that reduced the number of refugees hosted, and hence the size of grant available. But setting aside the feasibility of such a fund, the modelling exercise demonstrates that countries like Iran and Uganda, which include refugees in national systems, are currently taking on far more than their fair share of the responsibility for refugee education, and some richer countries are taking on far less.