In this blogpost, Dawit T. Tiruneh, University of Cambridge UK, and Tebeje Molla, Deakin University Australia, shine the spotlight on challenges in Ethiopia’s education system, with a focus on secondary education. This blog was originally published by Norrag on 18 April 2024.

The education system in Ethiopia has been grappling with a substantial crisis. Continuing civil war and political instability have disrupted the educational trajectories of millions of Ethiopian children. The school sector faces multiple challenges associated with quality, equity, and efficiency. As we showed in a recent article in The Conversation, for the second consecutive year, nearly 97% of secondary students (aged 18) who sat the national school leaving examination scored less than the 50% minimum proficiency benchmark established by the Ethiopian Ministry of Education. Furthermore, close to 90% of Grade 4 primary school children (aged 10) are unable to read and understand an age-appropriate text.

The rapid expansion of Ethiopia’s primary education (Grades 1-8) over the past two decades has substantially increased the demand for secondary education (Grades 9-12). Although the transition rate from primary school has been low, the gross enrolment ratio for secondary education has doubled in the last decade, from 23% in 2011/12 school year to 46% in 2021/22. Nearly four million students were enrolled in Ethiopian secondary schools at the beginning of the 2021/22 school year. Despite regional disparities in access to secondary education, the recent expansion has predominantly benefited historically marginalised groups, including girls, children from low-income families, and those from rural and pastoralist communities.

Despite the remarkable achievements in access, raising the quality of education amidst rapid enrolment growth has posed significant challenges. This piece highlights five issues affecting the secondary school system: an underfunded school sector, inadequate teacher preparation, narrow curricular provisions, abrupt policy changes, and widespread instability.

Underfunded Primary and Secondary Education

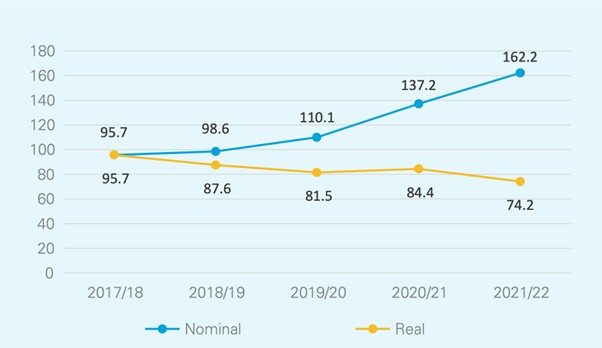

The scarcity of resources is a major cause of low levels of learning outcomes in Ethiopian schools. Most teachers work in large classes of up to more than 50 students and under poorly resourced conditions. Despite the rapid expansion of the sector, educational investment per student has declined in the last two decades. According to the World Bank, the expenditure on primary education per child stands at USD121 when adjusted using purchasing power parity (PPP), 78.6% below the sub-Saharan Africa regional average. With a 24% share of total national budget in 2020/21, education remains a priority in Ethiopia. However, primary and secondary education received only 44% of the total budget, compared to a 46% allocation to higher education. The government recently announced there would be an increase to the budget allocation for the sector. While this is encouraging news, the real budget value is undermined due to inflation. For example, the national education budget increased at an average rate of 14% in nominal terms between 2017/18 and 2021/22. However, the real value of education spending declined by around 23% between the same period (see Figure 1). Defence and debt servicing also persisted to overshadow allocations to social expenditures.

Note. Education spending in billion Ethiopian Birr; source, UNICEF (2022), based on data from the Ethiopian Ministry of Finance.

Inadequate Teacher Preparation

Over the past decade, the number of secondary school teachers has increased rapidly due to the expansion in student enrolment. However, the quality and relevance of initial teacher training programmes have been questionable. Many teachers are completing their pre-service training without acquiring the required content knowledge and pedagogical strategies, as evidenced by recent licensing exam results. A main challenge is the admission of underperforming candidates into teacher training programmes. In addition, the curricula of initial teacher training are not adequately tailored to the current composition of Ethiopian classrooms, which are characterised by students from diverse socio-eonomic backgrounds. Although there have been attempts to design and implement school-based professional development programmes to offer continuous support and improve the quality of teachers’ classroom practices, evaluations of these programmes have not been favorable. The absence of effective pedagogical strategies to enhance learning outcomes equitably can significantly affect students’ exam performance, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds, including girls, students from relatively lower income households and those from rural areas.

Narrow Curricular Provisions

The secondary education curriculum is academically demanding and closely tied to university entry requirements. In the new education policy (introduced in 2019 and formally approved in 2023), the government acknowledges that the school curriculum has not been well aligned with the evolving demands of the modern workforce and students’ needs. The curriculum will have to cater to the needs of a rapidly growing student population with a wider range of backgrounds, abilities, and aspirations than has previously been the case. Higher education attainment is low in Ethiopia. For the nation to catch up, secondary education needs to prepare students for university education, technical and vocational training, as well as the world of work.

Abrupt Policy Changes

In Ethiopia, public policy development is exclusive, lacking broad-based deliberation and consensus. Abrupt policy changes create confusion and disruption in the curriculum, assessment methods, and educational framework. Hence, teachers often find themselves adapting to new pedagogical approaches without adequate training or resources, impacting the quality of instruction. For example, in 2019, the government ended the Grade 10 national exam. The exam was a pivotal mechanism for streaming students into academic and vocational trajectories based on their abilities and preferences. Without this early tracking mechanism, providing targeted support in preparation for the Grade 12 national exam becomes difficult.

Widespread Instability

The education system has recently been affected by political volatility. With the ongoing ethnic conflicts, religious controversies, civil unrests, and increasing internal displacements, access to education has been disrupted for millions of children. In the school year 2023/24, over 2.6 million primary and secondary school students in Amhara region (nearly 42%) are out of school. A staggering 3,500 primary and 225 secondary schools are shut down in Amhara region due to the civil war, and some of the schools are serving as military camps. Close to a quarter of a million children are out of school in Western Oromia due to the armed conflict. In Tigray, millions of school children have missed years of educational opportunities due to the civil war that has rocked the region.

The ongoing political instability and conflicts in various parts of Ethiopia can reverse the considerable progress the country has achieved in terms of access, particularly to girls and children from rural areas. The challenge extends beyond access to include quality and equity in education and the overall wellbeing of students living in conflict areas. The disruption is leading to significant learning loss for millions of children and exacerbating existing inequalities as students from conflict-affected areas are left behind by their peers.

The tumultuous environment, characterised by ongoing civil unrest and war, is likely to create hurdles in the effective execution of crucial education reforms geared towards improving student learning outcomes.

The Way Forward: Don’t Waste a Crisis

Given these daunting circumstances, it is unsurprising that about 97% of Grade 12 students did not pass the national exam. Questions about the validity and difficulty levels of the national exam items may understandably arise. Nonetheless, examination scores provide valuable feedback on educational policies, curriculum, pedagogical practices, school governance and resources, and student growth. Genuine concern about the direction of the nation’s education system should not shy away from using this feedback to take bold and decisive actions.

As human capital is considered an important driver of a country’s economic growth, the learning crisis jeopardises Ethiopia’s future, necessitating urgent and transformative interventions. As one of us argued elsewhere, crisis makes swift reform possible to the extent that key stakeholders seize the moment with commitment and vision. We call upon all stakeholders, including state and federal governments, teachers and teacher unions, parents and communities, and international development partners, to unite in the rescue mission. Initiating inclusive policy deliberations at the earliest opportunity is imperative.

Thank you for your valuable insights. We need to struggle for the survival of our children. I hope I am part of that. Keep alerting!

Overall, I think the author’s point of view is great, however as a responsible citizen, I would want to bring up the issue of student evaluation. Are pupils being evaluated appropriately with appropriate exam levels in the existing educational system? In the educational system, student evaluations should adhere to established practice and procedure; otherwise, there may be a crisis. Thinking about other things might sometimes result in backlash. Therefore, please take the exam’s quality into consideration, unless there is a problem. Why do 97% of pupils have below-average scores? I do, however, value the author’s viewpoint and thoughts as a contribution.