This article was written by Dr Sharon Tao, Founder and Director of Level The Field. This blog was drawn from a Level The Field working paper, which aims to stimulate dialogue and new ways of thinking around the tensions, debates and challenges facing girls’ education.

If you have ever worked on a girls’ education programme, there is undoubtedly one question that you will have heard – be it from Ministry of Education (MoE) actors, teachers, parents, students, researchers, donors, even your own colleagues – which is, ‘what about the boys?’ At best, this question comes from a place of curiosity or scepticism. At worst, it is rooted in exasperation, resentment or backlash.

The aim of this blog is not to bemoan this question, nor the debate and impasse that often results. Rather, I aim to reflect on the process and assumptions that often lead to this impasse. I come from a position of having had to respond to the question myself and have found that clarifying a few key points can be incredibly helpful. Thus, I would like to pose some questions to girls’ education advocates (and all other interested parties) before they embark on the next ‘what about the boys’ debate. These questions aim to facilitate greater clarity during discussion in order to help identify gaps in analyses, make rationale more compelling, and support a common goal amongst all parties.

Overall, it is understandable, reasonable and quite frankly necessary to ask, ‘what about the boys?’ Which makes it all the more important to ensure that the related discussions and debates are as helpful and productive as possible. I hope that this blog will help with this end.

Question 1: Who is asking the question?

The ‘what about the boys’ question can come from a variety of people and perspectives. As such, it might be helpful to consider where the ‘asker’ is located within the education system, as this often indicates how their perspective may be motivating the question. It also gives an idea of how best to frame a response.

For example, at the global level, actors such as donors or economists may be looking at the ‘big picture’. When someone from this group asks, ‘what about the boys’, they may be focused on global targets and looking at global-level data that show that gender gaps in access and learning have significantly reduced.

At the country level, MoE officials may be looking at the national-level picture/data, often with limited budgets that never seem to meet all the priorities. When someone from this group asks, ‘what about the boys’, they may also be influenced by their own experience and observations of education in the country – although this varies, it is not uncommon for MoE actors to come from privileged groups in which they’ve observed girls to have excelled.

At the school and community level, when parents, teachers and boys themselves ask ‘what about the boys’, it often comes from a personal perspective – one that is not rooted in data sets, but rather from observations and a sense of unfairness that comes when a programme is seen to be giving more resource, attention and support to girls over boys.

Being mindful of who is asking ‘what about the boys?’, and how their worldview may be motivating their question, will start to point to how to best frame a response. The following questions and some reflections on them, aim to help with this effort.

Question 2: Which girls and boys are we referring to?

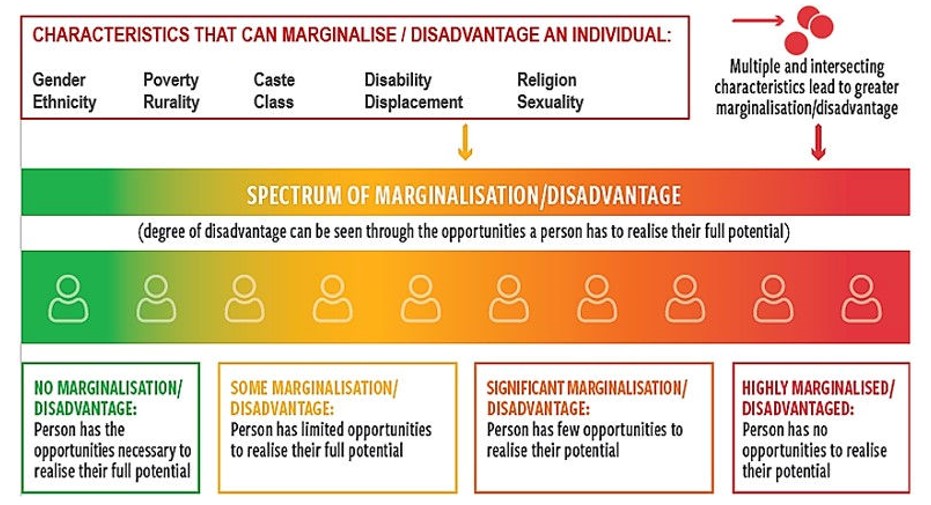

Most people understand what is meant by ‘girls’ and ‘boys’ in conversation, however, when discussing girls and boys within the realm of educational opportunities, a bit more clarity may be helpful. This is because there is a vast spectrum of advantage and disadvantage that girls and boys experience both inside and outside of school (see figure 1). At one end of the spectrum, there are girls/boys who have all the opportunities they need to realise their full learning potential. At the other end are girls/boys who have very few opportunities, if any. The majority of the population within a context usually falls somewhere in between.

When the question of ‘what about the boys’ is asked, it often refers to highly disadvantaged boys and their concerning outcomes, such as not learning, dropping out or failing to progress. Generally, these outcomes are implicitly compared to the general population, rather than to girls from the same highly marginalised group. This is not to say that these boys aren’t facing serious disadvantages due to poverty, rurality, caste, or displacement, amongst others; however, within these marginalised groups, any privileges that exist are rarely distributed equally amongst boys and girls. This is due to unequal gender norms, which disadvantage girls even further. Thus, those who are truly overlooked, are generally the marginalised boys’ sisters.

Given this situation, how can we make the ‘what about the boys’ debate more productive? If marginalised boys are the subject in question, it may be worth asking who these boys are being compared to – girls from the general population? Or girls from the same marginalised group? The former provides a less accurate comparison as population data will include children from more privileged ends of the spectrum. In order to more fully, and fairly, see who is being left behind, comparisons need to made with girls from the same background as the boys in question. By doing so, it is likely that disadvantages will be further magnified for girls due to unequal gender norms.

The best way to demonstrate this is to look at educational outcomes/data that have been sex-disaggregated by the poorest wealth quintile, rural location, and any other background characteristics available. At the school level, this disaggregated analysis could also be had by comparing disadvantage between boys and girls from within the same family, as opposed to the broader school or community population.

It should be noted that this is not meant to be a competition of disadvantage. However, in order to better debate the point of who is the most overlooked and thus might need to be prioritised, it may be helpful to be clear about exactly which boys and girls are being referred to, and whether the comparison being made is fair.

Question 3: What do we mean by ‘girls are doing better’?

There are a number of indicators that are used to gauge progress in education, such as enrolment, test results, and completion of primary/secondary, amongst others. For some of these indicators, global and national-level data appear to show that girls have caught up with boys and in some cases, are doing better. However, it may be worth asking:

1) which girls and boys are not included in these data?

2) are these indicators giving the whole (or enough of the) picture?

Generally speaking, most education indicator data that is reported by MoEs automatically excludes girls and boys who have dropped out of school because they are no longer in the MoE’s remit – they are ostensibly invisible to the education system and its data. Although there are laudable efforts to address this situation, we should be mindful of these gaps. Global/national education data only capture progress for children who are enrolled in school, which include those at the more privileged end of the spectrum, but not those at the other end who have dropped out. This is not to dispute the significant gains made by girls within these populations. Indeed, there are many girls who feature at the top of national exam league tables. However, we cannot use these exemplars to generalise across all girls. This is because these exemplars likely come from the more advantaged end of the spectrum, which is not representative; and secondly, because there are large numbers of out-of-school girls not being counted as part of the general population of girls.

In addition to considering who is missing in the data, it is also worth considering what age the data are reflecting. That’s because unequal gender norms – such as girls doing excessive domestic chores, being vulnerable to sexual harassment/violence, or being married early – will have more of an effect on girls’ educational outcomes as they get older. Thus, indicators taken at the primary level such as foundational literacy/numeracy, are generally more reflective of a level playing field between girls and boys. From the ages of 5 to 7 years, young girls will experience less gender norm disadvantage and as such, can do as well as or better than boys on assessments for early grade reading and maths. However, as these girls get older and unequal gender norms take hold, their outcomes will start to decline.

This begs the question, should we be striving for parity of outcomes or parity of enabling factors? As noted, parity of educational outcomes have the potential to mask things like exclusion and life stage. A more telling picture would be whether girls/boys from the same background are afforded equal levels of power, respect, participation, resources and safety, as these are just some of the enabling factors that allow a person to realise their full learning potential. However, as noted earlier, gender norms often underpin unequal treatment of girls, particularly in marginalised groups, which can lead to a very limited share of enabling factors and thus, poorer outcomes.

Given this situation, how can we be more productive when someone states, ‘girls are doing better now, so what about the boys?’ When conclusions and generalisations like these are made, it might be helpful to interrogate the data/evidence that underpin these interpretations. Who is missing from the data? Is the exemplar representative? Will outcomes for young girls look the same in 5 to 10 years? It may also be helpful to note that educational indicators are only one part of the picture. If we really want to see if girls are ‘doing better’, it may be worth asking whether they have equal or more power, respect, participation, resource and safety than boys from a similar background.

Question 4: What is intended when programmes focus on girls?

Generally speaking, when education programming has a focus on a particular disadvantaged group, such as refugees or children with a disability, the aim is often to make up for their significant disadvantages by providing extra support, particularly in contexts where there is none. Such an aim is no different for marginalised girls. However, this aim is not always clear because: 1) the short-hand term ‘girls’ education’ suggests all girls; 2) even if the term ‘marginalised girls’ education’ were used, there would still need to be significant clarification regarding what is meant by ‘marginalised’.

So when ‘what about the boys’ is asked, one way to frame the aim behind a girls’ education initiative is to take out the word ‘girls’ and ask the following: Do all the children in this context have the same opportunities to realise their full learning potential? If not, is that what we would ultimately like to see – everyone realising and contributing to their full potential? If so, who has the most disadvantage or ‘unequal playing field’? Should they be prioritised?

Framing a (girls’) education initiative as one that tries to level an unequal playing field, starts to signal that it is not inherently aiming to privilege girls to the detriment of boys. Rather, any extra support is trying to make up for multiple layers of disadvantage, which includes unequal gender norms that tend to disadvantage girls further.

Overall, when girls and boys have an equal playing field, both in education and life in general, everyone will benefit. The multiplier effect that comes with gender equality means that families will be better off, people will be healthier, there will be less violence and more security, and economies will develop. Which makes levelling the field a goal well worth aiming for.

The way forward: An opportunity to debate better

In the midst of ever increasingly frustrating debates, it is hoped that these reflections regarding the ‘what about the boys’ debate will facilitate more productive ways forward. Suffice it to say, it is important to acknowledge critical and contrary perspectives; but it is also necessary to show the gaps and omissions within them. This blog has highlighted some ideas that will help to do so. In summary:

- There is a spectrum of advantage/disadvantage that indicates the degree to which girls and boys have the opportunity to realise their full learning potential. If a select group of girls or boys are highlighted as an exemplar – either for doing well or doing poorly – it is not correct to use these exemplars to generalise or compare across the rest of the population. Disadvantaged boys or successful girls need to be compared to the opposite sex with the same background characteristics (i.e., those at the same point on the spectrum). Otherwise, any gender gaps that are highlighted (or disputed) are inaccurate and not entirely fair.

- Temporarily taking out the term ‘girl’ or ‘gender’ from a programme/policy title can make the aim clearer. If the aim is indeed to level the field for those with greater disadvantage, so that they have more opportunity to realise their full potential, then prioritisation doesn’t necessarily start with girls, but rather with those at the most disadvantaged end of the spectrum. Generally, this will entail marginalised groups; however, it is imperative to look within these groups, as unequal gender norms will be magnified and will always disadvantage girls further than boys.

- Reframing girls’ education interventions as ways to level the field may help mitigate interpretations of unfairness. Unequal gender norms – like early/forced marriage, sexual harassment, or prioritising sons if family poverty is paramount – put some girls at a significant disadvantage, which is why girls’ education interventions try to address these. However, activities are not always explained in this way. So, when bursaries, uniforms, or books are provided to address the opportunity cost for a poor family to send their daughter to school, there is often an interpretation that all girls are receiving preferential treatment over boys. Those implementing such activities should take great care to explain/frame them; and note that a number of girls’ education interventions, like gender responsive pedagogy and reducing violence, significantly benefit boys too.

- Although macro-level education data and indicators are important, they do not provide a complete picture. Be aware of who is missing in the data (i.e., excluded children) and that the data are a snapshot in time (that may not capture how disadvantage develops with age). This is not to say that these data/indicators are not valuable, but given the blind spots, they should not always be valorised. There is also the potential for complacency when the data indicate parity. If we truly want to see if girls and boys have parity in realising their full learning potential, we should instead look at the degree to which they are afforded equal amounts of enabling factors, such as power, respect, resource, participation and safety.

That said, when/if girls and boys do indeed have equal levels of power, respect, resource, participation and safety – no matter what their background – everyone will benefit, on multiple levels. However, the process of levelling the field in order to get to this point is not always clear and can unfortunately be misunderstood. Which is why engaging in productive ‘what about the boys’ debates are imperative. Hopefully, this blog has helped with this end.