This blog was written by Moses Oketch, Caine Rolleston and Cesar Burga Idrogo, University College London (UCL).

Context of the problem

Understanding teachers’ contribution to raising learning outcomes at scale is important for informing policy on teachers and teacher development. Much of the research dedicated to assessing the contribution of teachers to their pupils’ progress in quantitative terms uses what is known as ‘value-added modelling’ (VAM). Value-added is typically estimated based on students’ measured learning gains over a course of a fixed period such as an academic year.

Unfortunately, value-added estimates generally describe a black box of mechanisms and do not identify which specific teacher practices and/or interactions with pupils lie behind students’ progress. Therefore, it is worth asking: can evidence on pupil progress be used to understand teacher quality or to inform teacher policy? In this blog, we examine this in the context of Ethiopia. We argue that VAM offers important potential, but that findings need careful contextualisation.

While data suited for value-added analysis are rarely available in low- and middle-income contexts, we are able to make use of such data for Ethiopia, collected by the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme.[i] We use data from pupils in primary Grade 4 collected in 2018-19, which includes data on learning outcomes in mathematics collected both at the beginning and end of the academic year as well as rich information on pupils’ backgrounds.

Ethiopia is a particularly interesting case study. While important reforms to improve both equity and quality of basic education have been implemented since 2012, learning outcomes declined between 2012 and 2018. One of the key reasons for such decline is the change in composition of students in classrooms, as more children from disadvantaged backgrounds have been enrolled in schools as a result of the reforms. Resources are very limited and therefore efficient use of them is of utmost importance.

Better understanding of the role of teachers in supporting students’ learning progress, particularly disadvantaged pupils, could, in principle, contribute significantly to the design and implementation of reforms. We reflect on the potential of VAM in this connection.

What does evidence on VAM show for the Ethiopian context?

Using data with repeated measures on a learning assessment with a common scale, we can calculate a simple ‘progress score’ for each pupil and average this for the teacher (class level). This provides a basic measure of the learning gains associated with each teacher in a school survey dataset, such as the RISE Ethiopia data. Having done this, we grouped teachers into three categories according to average pupil learning gains – high (top 30%), medium (middle 40%) and low (bottom 30%). We may expect that higher ‘quality’ teachers teach pupils who make more progress, but of course progress also depends on many other factors, such as pupils’ own confidence and motivations, the affinity they have with their teachers, their prior knowledge, the support offered at home, the overall school conditions, and many other things. Progress may also depend on a pupil’s starting point. For example, it may be ‘easier’ to progress from a lower base, depending on the design of the learning assessment.

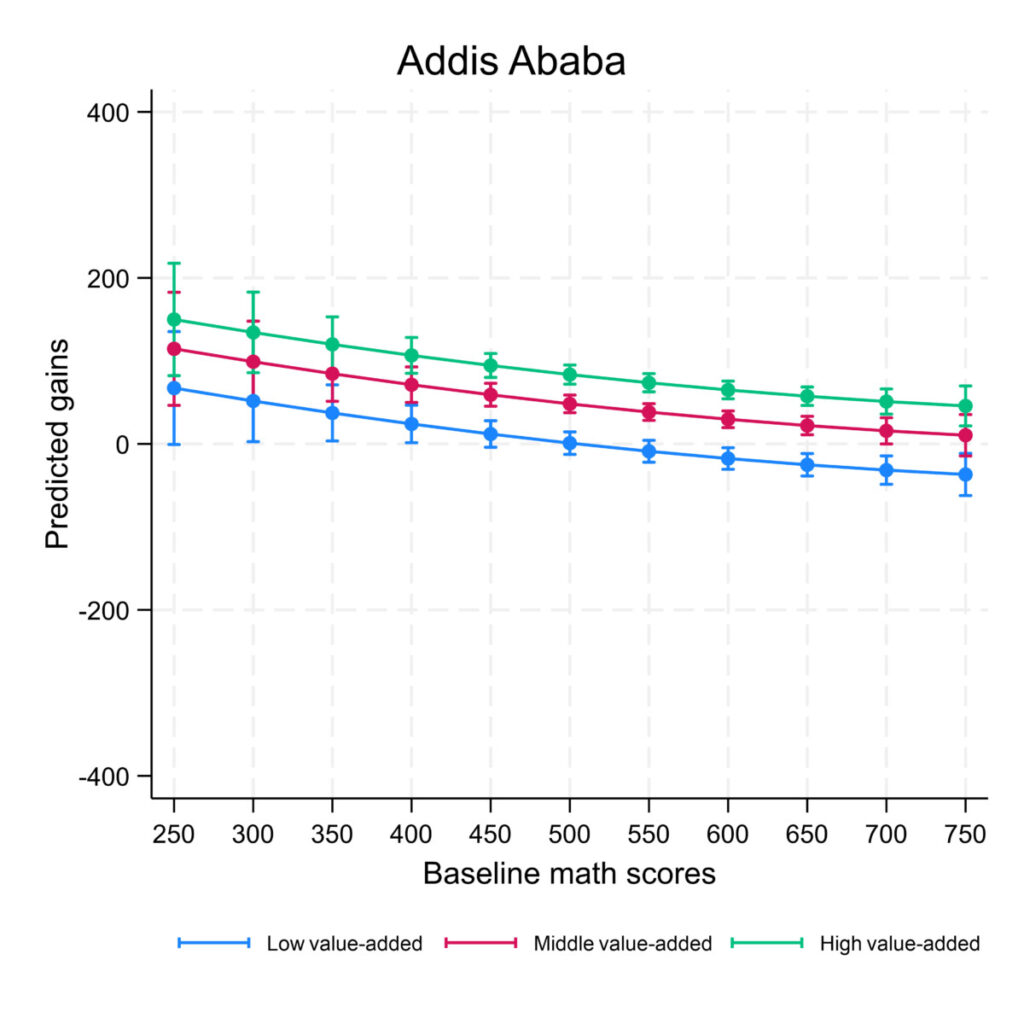

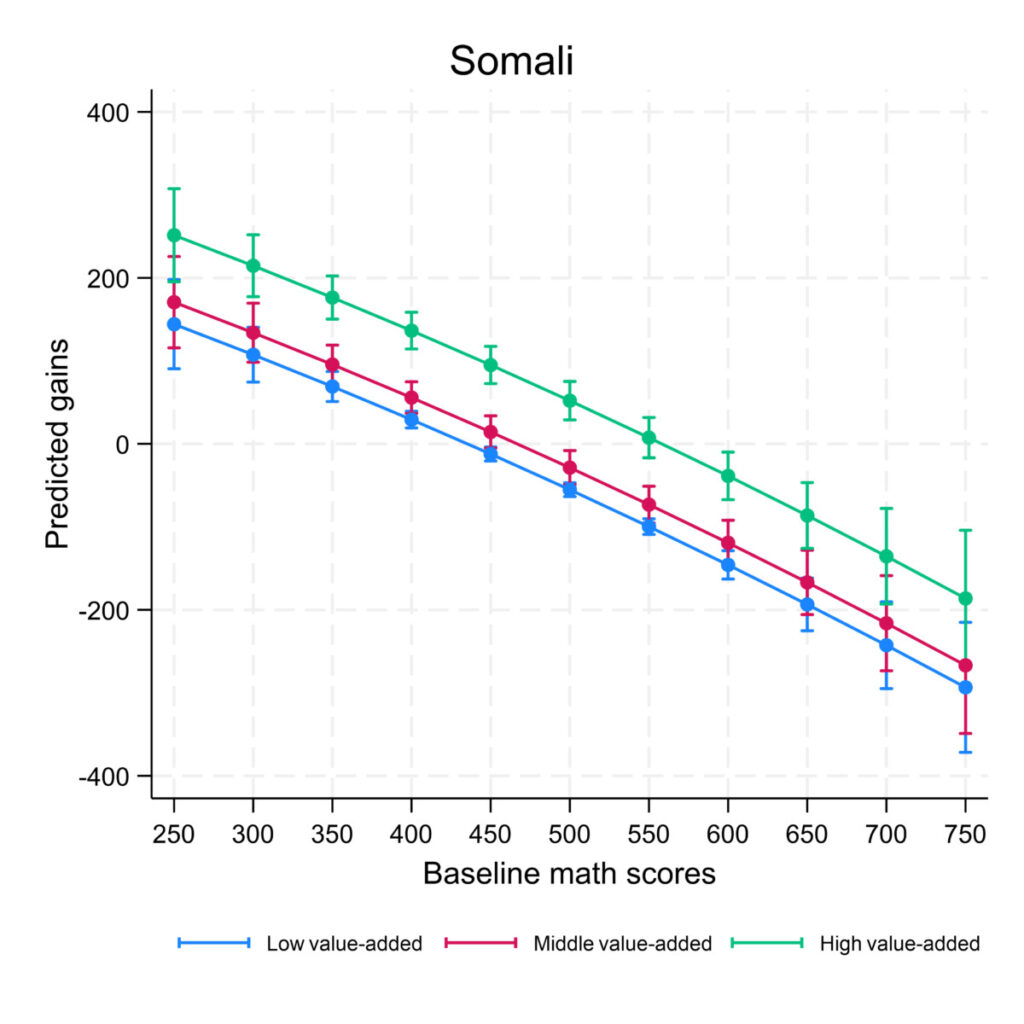

To better illustrate this, we present in Graph 1 the predicted learning gains for pupils in two regions – Addis Ababa and Somali – while accounting for their individual characteristics.

Graph 1: pupils’ expected learning gains by region and teacher

We can see that high performing students are expected to make more progress in Addis Ababa compared to Somali, regardless of the group of teachers. Conversely, low performing students are expected to have greater learning gains in Somali.

Thus, differences in expected outcomes by prior achievement and region are bigger than differences by groups of teachers based on unconditional VAM. This supports the idea that a contextual approach, accounting for pupils’ backgrounds, is important for having a more accurate diagnostic – both of pupils’ learning gains, and of the contribution of the teachers.

Comparing VAM to a contextual measure of pupils’ progress

We now compare this evidence to a more sophisticated measure – the difference between pupils’ actual progress and expected progress based on their background characteristics and test scores at the start of the year.

After estimating this contextualised measure of pupils’ progress, we construct an average difference between actual and predicted progress scores at teacher level. We then group teachers in two categories: those whose pupils’ actual averaged progress is equal or above its expected value and those whose pupils’ averaged progress is lower than expected.

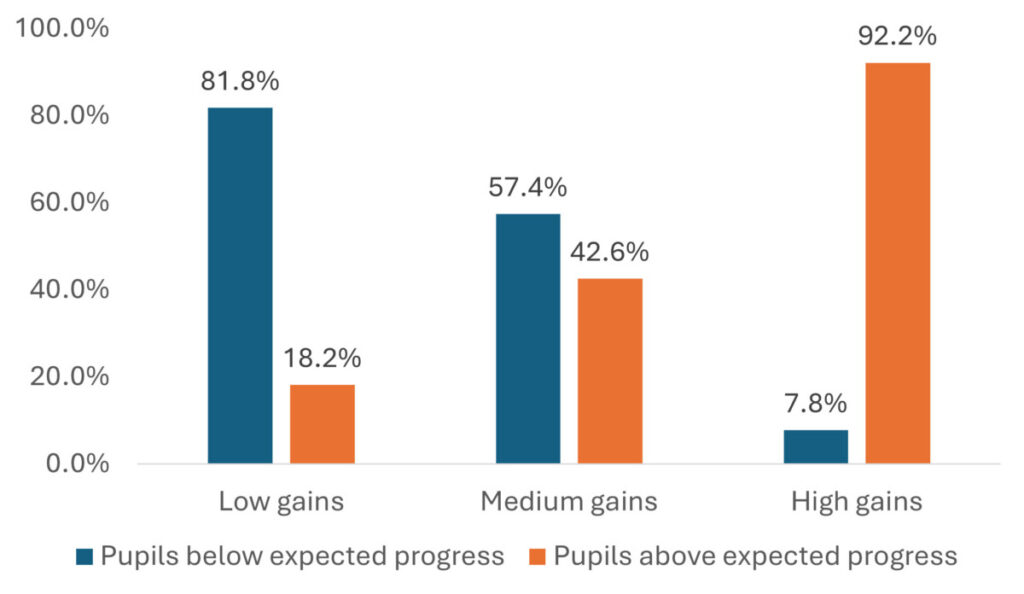

We compare teachers in Graph 2 according to their pupils’ average and expected learning gains. As we see, 18.2% of “low gains” teachers have pupils that meet their expected outcomes. In the case of “medium gains” teachers, the percentage rises to 42.6%.

Graph 2: Teachers by pupils’ average learning gains vs expected gains

These differences are not negligible. Evidence that teachers face pupils from different backgrounds (region, prior achievement, etc.), and do not account for their background can lead to a misjudgement of teachers.

The implications of this misjudgement are particularly important in the context of policy-making. If we consider implementing a teacher development programme focusing on “low gains” teachers, about one in five teachers would receive it even when their pupils are actually achieving at least their expected outcomes. Conversely, the rest of teachers would be excluded from this programme, although for a considerable proportion (principally from the “medium gains” group), their pupils are not reaching their expected outcomes.

Limitations and possibilities for research

We have used RISE longitudinal data to explore the extent to which VAM can be informative for teachers’ policy. We have shown that, while unconditional VAM provides important information about pupils’ progress, it is not enough to judge teachers’ performance as their pupils’ progress might depend on different factors (prior achievement, the region, etc.) not considered by simply looking at learning gains. Thus, a contextualised approach that accounts for all these factors seems to be more adequate, specially to inform policy on teachers’ development.

Although we have provided some evidence to support a contextualised approach in this blog, we must be careful not to interpret our outcomes in a causal way. Important challenges faced by pupils, such as the unavailability of educational resources at home, or the quality of school infrastructure, have not been included in our model. Neither have we included important challenges faced by teachers, such as large class sizes, or pupils’ motivation.

Further research could improve this contextualised approach by accounting for these factors. It could also explore the relationship between teachers’ practices development in terms of training, years of experience, knowledge of the topic, or pedagogical strategies, and pupils’ achievement of their expected gains, both on average and at an individual level.

Acknowledgments

This publication is possible thanks to RISE Ethiopia, and funding from FCDO. We would like to express a special acknowledgement to Dr Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh, Dr Mesele Araya and Dr Ricardo Sabates. Their support with the data and their comments were very useful in the development of this work.

[i] RISE Ethiopia data is a longitudinal data collected by the Ethiopian Development Research Institute (EDRI) and the RISE programme. It has information of pupils at grades 4 and 8, at the start and the end of the year. Data collected includes pupils’ achievement, household’s background, and other different individual characteristics. It also includes information about teachers and schools.