This blog was written by Shweta Chooramani.

Migrant STEM students face significant challenges due to the lack of Multi Lingual Education (MLE) innovation, as language proficiency is crucial for academic success (Schleppegrell, 2004). Decolonising STEM education demands questioning the assumption that English-medium instruction (EMI) is the sole path to STEM success. To achieve this, we must ask: Are sufficient resources being allocated to diverse language policies, teacher development, and pedagogical innovations specifically designed to support migrant children?

Understanding MLE needs of migrant children

The 8th schedule of the Constitution recognises 22 official languages, 121 languages and 270 mother tongues (Census of India, 2011). Despite India’s linguistic diversity, “only 0.4% of the education budget” is allocated for language development, and “merely 2-3% for teacher training” (National Education Policy, 2020). The limited funding for STEM education in regional languages disproportionately impacts migrant communities. Inadequate teacher training for MLE and lack of creativity in STEM hinders policy implementation for migrant children.

Hence, there is a need to reimagine the migrant narrative framework. There is an urgent need to view MLE and STEM competencies as a function of Economics, Labour, Culture and Skills, and not just Education. I urge policymakers to match the aspirations of the National Education Policy (NEP) with practical realities at the school level.

55% of India’s working children are from five states, with Uttar Pradesh and Bihar comprising 32% (International Labour Organization). Children migrate to regions where schooling languages diverge from Hindi, and find employment in sectors like the cotton, construction, leather, and silk industry. MLE innovation’s absence disproportionately impacts migrant students, especially in STEM classrooms, where a mix of English and local languages is used.

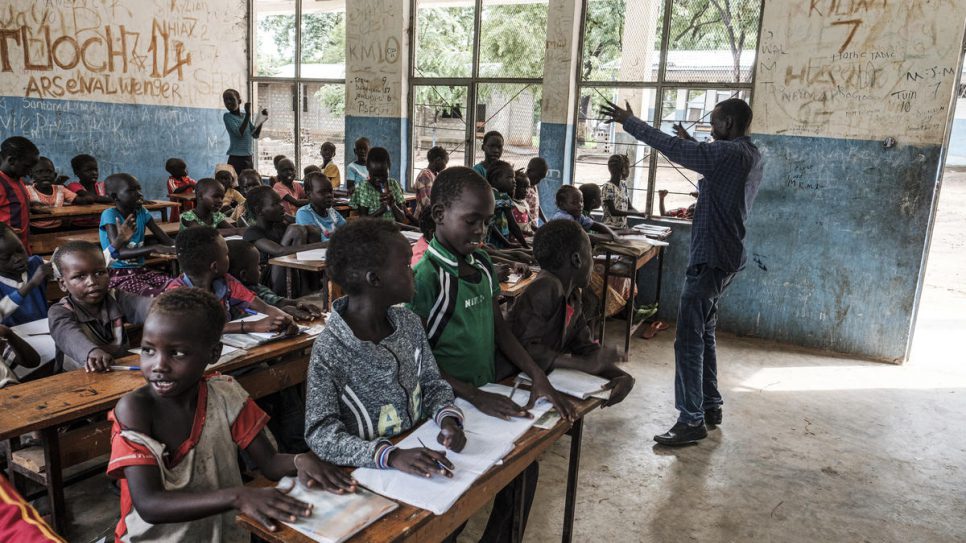

Therefore, language proficiency is critical for scientific discourse (Schleppegrell, 2004; Vygotsky, 1962). Teachers overwhelmed by diverse linguistic backgrounds struggle to cater to individual needs, hindering content acquisition and reinforcing negative stereotypes such as ‘broken English’ or ‘silent watching’ (Banilower et al., 2013; Van Laere et al., 2014). English dominance in STEM perpetuates an unfair advantage, leaving behind states with emerging second languages. To truly level the playing field, we desperately need comprehensive teacher training and innovative teaching methods to create inclusive learning spaces for all students.

Reimagining migrant narrative framework: MLE and STEM education as a function of Economics, Labour, Culture, and Skills, not just Education

Despite India’s diversity of languages, and despite the Right to Education Act of 2019 and the 2020 NEP’s emphasis on mother tongue instruction, our educational institutions remain woefully ill-equipped to accommodate this linguistic diversity. While the NEP recognises the crucial role of “language development”, it is tragically underfunded.

This blatant disregard for linguistic needs severely hinders the effective implementation of language policies and STEM pedagogies. To rectify this, the government must urgently allow hiring teachers proficient in the destination site language, mother tongue, and English.

Secondly, we need to ask leaders: does India possess the necessary administrative processes to effectively implement MLE in STEM education? While innovative methods and meagre library grants offer limited support (Indian Rupees 5,000-20,000), the 10-day “bagless” period and expanded “Ek Bharat Shrestha Bharat” initiatives are crucial. However, the glaring disconnect between policy and practice continues to marginalise countless children due to linguistic barriers.

Resource-smart solutions for migrant children

Teachers have the power to make learning through healing happen. Migrant children tend to experience undue amount of mental stress due to forced displacement, food and housing insecurity, lack of belongings, vulnerability to sexual harassment in the absence of both parents at unusually long work hours or relying on informal childcare, and violent episodes due to socio-economic-emotionally draining deficit situations. It is likely the teacher might be the only avenue of meaningful human interaction for a migrant child to have a conversation with throughout the day.

At the foundational level, to build teachers’ agency there is a need for creative professional development avenues that expose them to newer perspectives and improve their Science Process Skills along with pedagogical approaches (Li, Zhang, Yu, et al, 2024). RTI’s toolkit Bridging Language and Learning: Empowering Multilingual Learners in STEM is a great tool for practitioners who want to develop STEM competencies. For instance, traveling from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to developed states of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Gujarat and Delhi and developed countries.

The Indian movies “Nil Battey Sannata” and “Hichki” showcase the power of mother tongue instruction and role of teachers in motivating low-performing STEM students. Further, there is a need to introduce traditional education practices from Indian culture for improving critical thinking required for STEM education.

To combat this, as a policy researcher, I propose two ways:

- “Science Reflective Journaling” combined with “designed space” can be a great tool for teachers to promote MLE and STEM (Towndrow, Ling, & Venthan 2008). Because the child needs to feel socially accepted first in a warm welcoming environment, the love for learning needs to be nurtured before the child is mentally ready to learn difficult STEM concepts. Room to Read underscores the importance of local language literacy for STEM learning in India. Evidence also suggests, by fostering classroom interaction, language scaffolding, and leveraging students’ native languages, we can sustain curiosity in STEM subjects (Osborne, 2007; Gibbons, 2002). Learning STEM in designed space fuels curiosity by organising tours to science/history museums, laboratories, and factories. Following visits, students will complete mother tongue writing activities (essays, narratives, journaling, glossaries, storyboards) known to improve scientific inquiry and dialog.

- Foster a playful approach to STEM learning by including board games such as Chess, a “strategy game” originated during the 6th Century in the Gupta Dynasty, India. Ample research recommends Chess as an effective low-cost STEM intervention for improving cognitive outcomes, problem-solving and social inclusivity in a variety of diverse multi-lingual geographic settings including rural Tamil Nadu, India. In Malawi it has helped combat child labour. Even in developed countries like Germany, Spain, Italy and Denmark, evidence suggests creative complex problem-solving through playing chess improves scientific coherence, reading comprehension and algorithmic understanding for STEM, and is highly encouraged as an assistive learning tool.

Conclusion

The poor academic performance of migrant children, specifically girls, and underrepresentation in STEM fields from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are not rooted in a lack of ability but rather systemic failures in MLE, exacerbated by labour law violations and language disparities. To address this global issue, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, which have historically benefitted from exploitation, should provide reparations to support marginalised communities and promote equitable education systems.