This blog was written by Ha Yeon Kim, Senior Advisor, and Monazza Aslam, Research Director, Data and Research in Education Research Consortium (DARE-RC) in Pakistan.

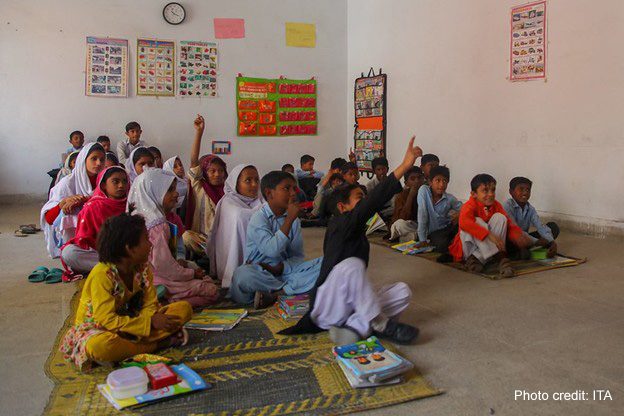

Pakistan just has become the ground zero for one of the world’s largest public school outsourcing experiments. In three phases, the Government of Punjab plans to transfer nearly 14,000 public schools—approximately 30% of all its schools—to NGOs and private operators via Punjab Education Foundation (PEF). This bold initiative aims to fix the broken education system, riddled with a long list of problems, including inefficient school management, poor infrastructure, outdated curricula, teacher shortages, millions of out-of-school children, and poor learning outcomes.

But can this bold move deliver on its promises? The stakes are high, and so are the concerns. Critics have warned of hidden costs, potential decline in quality due to cost-cutting measures, lack of accountability and oversight, and risk of exclusion of the most marginalised populations and communities.

Whilst Pakistan has a long history of engaging in different types of public-private partnership (PPP) arrangements, the sheer scale of outsourcing in Punjab is unprecedented. The evidence to back such reform at a staggering scale is, at best, limited. Globally, research on outsourcing public schools—typically where a private provider takes over the management of a government school—shows inconsistent impacts. For example, Liberia’s school outsourcing experiment improved student learning outcomes but came at the cost of excluding marginalised groups like more disadvantaged girls and students from overcrowded schools. It also exceeded the projected per-pupil budget by more than double.

Closer to home, there are very few available high quality studies that examine the direct impacts of this type of PPP arrangement. The handful of studies that do exist have shown no significant improvements in student learning outcomes. Similarly, research on various other forms of PPP in Pakistan—including school subsidies, school vouchers, and new schools in marginalised communities—has shown modest impacts in increasing access in certain cases, with little to no effects elsewhere.

The presumed advantage of private school management also seems uncertain. Research on the “private school premium” in Pakistan has shown that the quality of education in private schools wildly varies, and so does the added value of private schooling on student outcomes. Given the scale of Punjab’s outsourcing policy, this variability is likely to be amplified, posing a critical challenge: ensuring consistent quality across thousands of schools managed by diverse operators.

What will it take for success?

To make this ambitious reform work at scale, Punjab must address key challenges from the outset. Based on existing evidence, the following would be important considerations for the PEF and the Punjab government:

- Equity is not optional. Robust safeguards must be built into contracts as well as in the monitoring and evaluation process to protect marginalised groups. This could include guaranteed enrolment quotas for underserved communities and targeted support for marginalised children.

- Cost expectations should be realistic. Quality education does not come cheap, and achieving efficiency takes time. Both Liberia’s experience and early Punjab data show expenses exceeding projections. Budgeting for 150-200% of the initial estimates, at least for the first year, may be necessary.

- Active oversight is key. Outsourcing does not mean hands-off. Proactive oversight and monitoring to enforce the minimum quality standards and safeguards are requirements, not an option.

- Transparency trumps expediency. Transparent bidding processes, equitable school selection criteria, and financial accountability measures are critical for maintaining public trust—especially for such large-scale privatisation efforts.

- Standardisation matters. Private operators must align with public school curricula and standards. Misalignment could result in poor outcomes, with teachers and students bearing the brunt. The government must ensure that curricular standards are met and that teachers are well-qualified and adequately trained.

- Communities must be engaged. Building trust with local communities is vital. Operators should involve teachers, parents, and local leaders in decision-making processes to foster ownership and support.

A path forward for Punjab

Punjab’s school outsourcing policy is a bold attempt to transform its struggling education system through innovation and public-private collaboration. While the initiative holds promise—particularly for increasing access—it also carries significant risks, especially for marginalised children and communities often overlooked in large-scale reforms.

To succeed, policymakers must adopt a proactive approach that prioritises equity and inclusion, ensures rigorous oversight to uphold quality, and actively engages stakeholders, including marginalised communities. Private operators must be held accountable not only for outcomes but also for their efforts to reach and serve the most vulnerable populations.

This is more than an experiment—it is an opportunity to redefine education delivery in Pakistan. By learning from global experiences and tailoring solutions to its unique context, Punjab can set an example for others facing similar challenges. Success will hinge on thoughtful and inclusive execution, requiring commitment from both private operators and policymakers to ensure no child is left behind in this transformation.

The rising trend of outsourcing public schools’ results in very low salaries for teachers, which will have serious consequences for teachers’ professionalism and status. The proponents point to better students learning outcomes despite low payments. How can we ensure better teachers’ pay?