This blog was written by Siddharth Pillai, Education Programme Advisor for Street Child. The author would like to thank his colleague Ramya Madhavan, USAID-Global Reading Network and the ALIGN Helpdesk at Education Development Center (EDC) for their support and contribution to the article. In this blogpost, Siddharth argues that the Mathematics curriculum of Sierra Leone is overly ambitious in terms of coverage, pacing and progression contributing to flat learning profiles, as revealed by an analysis using the Global Proficiency Framework (GPF) for Mathematics. He proposes ALIGN for Minimum Proficiency process as a useful tool to recentre the curricula and align other pedagogical inputs to achieve minimum proficiency levels for mathematics.

Introduction

7 out of 10 learners in Grade 2 and Grade 4 in Sierra Leone cannot add or subtract 2-digit numbers (Ministry of Basic Senior Secondary Education, 2021). The proportion of learners who score zero in these tasks does not drop as learners progress from Grade 2 to Grade 4 (ibid.). There is growing evidence that shows that learners in low-income countries like Sierra Leone have a relatively flat learning profile (Pritchett & Beatty, 2012). Flat learning profiles indicate that learners learn far less with every additional year of instruction. One of the reasons for this has been attributed to an overly ambitious curriculum in terms of the coverage, pacing, and learning progression (World Bank, 2005), in addition to the composition of the curriculum. Here, curriculum coverage refers to the full range of curricular standards or learning goals learners are expected to acquire. Curriculum pacing is the speed at which these curricular standards are expected to be attained within the stipulated learning hours. Learning progression refers to the sequencing of teaching and learning expectations across age or grade levels and the order in which curricular standards are expected to be mastered by the learner.

A curriculum that covers too much, too early and too fast leads to learners transitioning from one grade to another without gaining mastery over the basic concepts. Only when there is conceptual and procedural mastery, the child can use the new learning effectively and flexibly and use it as a basis for further learning. Once basic competencies become automatic, there is more room left in the working memory of the child for active thinking and processing higher-order tasks (Belafi, Hwa & Kaffenberger, 2020). With limited remedial support, as the curriculum advances quickly, learners do not have the prerequisite knowledge to grasp more advanced concepts and hence the flat learning profiles. Pritchett and Beatty (2012) paradoxically claim that the pace of learning would be faster if curriculum and teachers were to slow down. In this article, the coverage, pacing and progression of the Mathematics curriculum of Sierra Leone (Grade 1 to Grade 3) is being analysed using the Global Proficiency Framework (GPF) for Mathematics. GPF defines important reading and mathematics-related knowledge and skills learners should develop in primary and lower secondary school. It also describes the minimum proficiency levels learners are expected to demonstrate, with respect to the defined knowledge and skills, at each grade level from grades one to nine.

Too much, too early, and too fast: Alignment of the Mathematics curriculum of Sierra Leone with the GPF

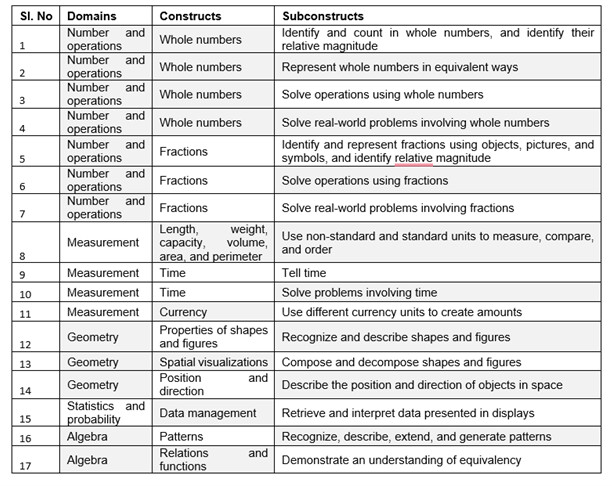

GPF represents a global consensus on the knowledge and skills learners must acquire at each grade level, and it qualitatively describes what learners who are not meeting, partially meeting, meeting, or exceeding expectations can do in relation to each skill at each grade level. While the GPF has its limitations, it is a useful tool for any system that is taking transformative steps to prioritise learning. In countries like Sierra Leone, grappling with low learner performance, recentring curricula and teaching is understood to be part of key actions to drive system transformation (Pritchett, Newman & Silberstein, 2022). To understand the alignment between the GPF and the Mathematics curriculum of Sierra Leone, a qualitative content analysis of the Mathematics curriculum and courseware of Sierra Leone (Grade 1 to Grade 3) was done against the Global Proficiency Descriptor (GPD)[i] for “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency”. 84 GPDs linked to the Sierra Leone Mathematics curriculum and courseware for lower primary grades were identified. These belonged to 5 domains, 11 constructs and 17 subconstructs as shown below.

Table 1: Domains, constructs and subconstructs of the GPF linked to the Sierra Leone Mathematics curriculum and courseware for lower primary grades

A qualitative content analysis of the curriculum and courseware of Mathematics for Grade 1-3 led to the identification of the following patterns:

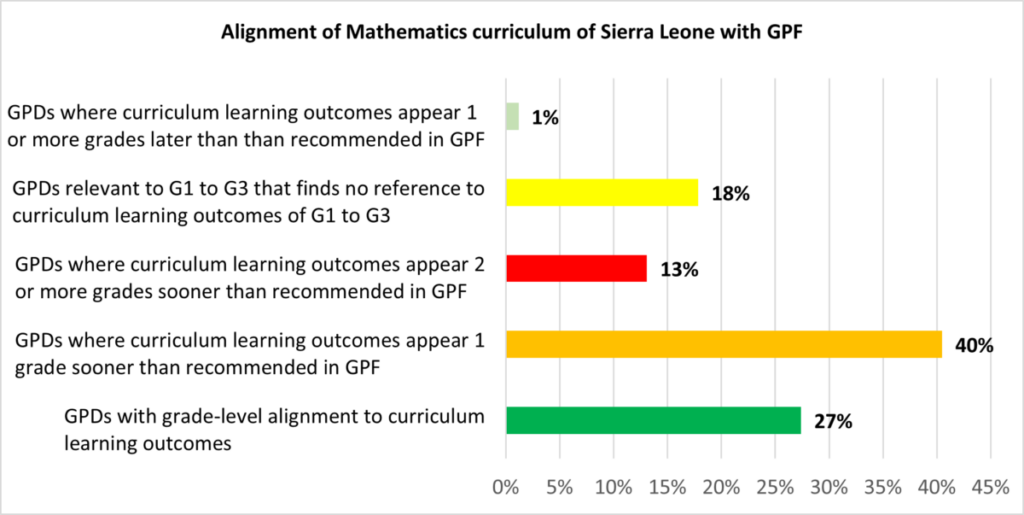

- For 23 out of the 84 GPDs, GPD and curricular standards are aligned at the respective grade level. For instance, the GPD “Count in whole numbers up to 30” is tagged at Grade 1 level in GPF and the same is included in the Mathematics curriculum of Sierra Leone for Grade 1.

- For 34 out of the 84 GPD (40%), curricular standards appear one grade sooner than the grade-specific GPD in GPF[ii]. For instance, “Count in whole numbers up to 100” is a Grade 2-specific GPD in GPF. However, this is the curriculum learning outcome for Grade 1 as per the Mathematics curriculum for Sierra Leone. [In this article, grade-specific GPD refers to the descriptor for “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” for that particular grade as per GPF. For instance, the GPD “Count in whole numbers up to 100” is referred to here as a Grade 2-specific GPD, as this specific GPD is mentioned in GPF at Grade 2 under the “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” category. The analysis here is done using GPDs under “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” category with the intention that countries grappling with low level performance should maximise conditions for all learners to achieve minimum proficiency, rather than aim for fewer learners to exceed global minimum proficiency.]

- For 11 out of the 84 GPDs (13%), curricular standards appear two or more grades sooner than the grade-specific GPD in GPF.

- 15 out of the 84 GPDs (18%) aren’t referred to in the curriculum – in spite of being prescribed for Grades 1 to 3 in order to “Meet Global Minimum Proficiency”. Only 1 out of 84 GPDs, the associated learning outcome in Sierra Leone curriculum, appear one or more grades later than the grade-specific GPD in GPF.

Thus, as shown in Figure 1, the alignment between the GPF and the lower primary curriculum for Mathematics is less than 30%.

Figure 1: Alignment of Mathematics curriculum of Sierra Leone with GPF[iii]

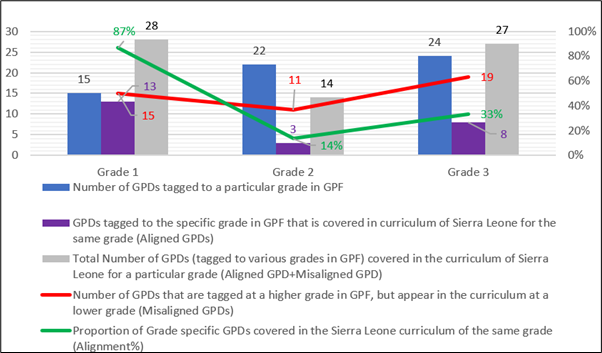

Figure 2 below shows the alignment of Sierra Leone curriculum with GPF across grades and indicates the need to review and revise the curriculum and courseware by reassigning some of the current Grade 1, 2 and 3 curriculum standards to higher grades as per the GPF. While the curriculum is to spiral, when learning outcomes are expected to be attained sooner than suggested by GPF, there is the risk of misaligned teaching and teachers rushing through curricular content.

Figure 2: Alignment of Mathematics curriculum with GPF across grades

While the alignment with respective grade-specific GPD is high in Grade 1 (87%), this alignment drops significantly in Grade 2 (14%) and Grade 3 (33%). If we look at the GPDs that appear one or more grades sooner in the curriculum than what is recommended by GPF, the highest number of them appears in Grade 3 (19), followed by Grade 1 (13) and Grade 2 (11). The following are some grade-specific observations from Figure 2:

- Grade 1: Issues related to both curriculum coverage and sequencing are to be addressed here. The curriculum for Grade 1 is linked to 28 GPDs (13 aligned GPDs + 15 misaligned GPDs), against the required 15 which shows the curriculum to be highly ambitious in terms of coverage. Such highly ambitious curriculum coverage increases the pacing, detrimentally affecting learning. Moreover, as more than half of the GPDs covered in the Grade 1 curriculum (15) are tagged to higher grades in GPF, issues related to learning progression have to be addressed as well.

- Grade 2: The Grade 2 curriculum links to 14 GPDs (3 aligned GPDs + 11 misaligned GPDs), against the required 22. The curriculum coverage is lower in Grade 2 when compared to GPF, which can be resolved by reassigning some of the abovementioned Grade 1 topics to Grade 2. Challenges related to learning progression are to be addressed here as most of the topics/units covered in Grade 2 curriculum are tagged at Grade 3 or higher in the GPF.

- Grade 3: Issues related to sequencing are to be addressed here. Most of the GPDs covered in the Grade 3 curriculum (19) are tagged at higher grades in GPF.

A detailed evidence-based gap analysis vis-a-vis the GPF is proposed here as the first step toward revision of the overambitious curriculum. The gap analysis and the subsequent curriculum revision shall form the basis for reviewing and improving the other three pedagogical inputs, namely Teaching and Learning Materials, Teacher Training, and Assessment. The ALIGN (Aligning Learning Inputs to Global Norms) for Minimum Proficiency Process tool could further support the Ministry of Education to align the curriculum and the related pedagogical inputs to the global norms maximising conditions for all learners in Sierra Leone to achieve minimum proficiency levels for Mathematics.

————————————-

[i] Global Proficiency Descriptors (GPD) – GPD in the Global Proficiency Framework (GPF) describes the exact measure of performance that a student needs to demonstrate to show mastery of a skill at a specific grade level. In the GPF, these descriptors are categorised further in terms of lower to higher proficiency expectations by grade level as follows a) Below Partially Meets Global Minimum Proficiency – The learner lacks the most basic knowledge and skills. As a result, they generally cannot complete the most basic grade-level tasks. b) Partially Meets Global Minimum Proficiency – The learner has limited knowledge and skills. As a result, they can partially complete basic grade-level tasks. c) Meets Global Minimum Proficiency – The learner has developed sufficient knowledge and skills. As a result, they can successfully complete the most basic grade-level tasks. d) Exceeds Global Minimum Proficiency – The learner has developed superior knowledge and skills. As a result, they can complete complex grade-level tasks.

[ii] In this article, grade-specific GPD refers to the Global Proficiency Descriptor for “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” for that particular grade as per GPF. For instance, the GPD “Count in whole numbers up to 100” is referred to here as a Grade 2-specific GPD, as this specific GPD is mentioned in GPF at Grade 2 under the “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” category. The analysis here is done using GPDs under “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” category with the intention that countries grappling with low level performance should maximise conditions for all learners to achieve minimum proficiency than aim for fewer learners to exceed global minimum proficiency.

[iii] The graph uses the phrase “GPDs where curriculum learning outcome appear 1 grade sooner than recommended in GPF”. This refers to the instance where the curriculum learning outcome of Sierra Leone appears 1 grade sooner than the grade linked to the Global Proficiency Descriptor for “Meets Global Minimum Proficiency” in the GPF.