This blog was written by Dr Oudai Tozan, who recently finished his Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge, researching the potential role of exiled Syrian academics and researchers in rebuilding the higher education sector of Syria.

On 8 December 2024, 6:18am, a 54-year brutal dictatorship in Syria came to an end, opening the chance for a historical shift in Syria’s political, social and economic future. Although the future in Syria remains uncertain, higher education is central to that future. Higher education has the potential to promote peacebuilding by addressing inequalities, teaching peace studies, promoting participatory learning, providing a space for research on peace-related topics, supporting economic recovery, and fostering social cohesion. What will be our role as Syrian academics in the diaspora in supporting higher education? How can the diaspora, local government and international actors contribute to create a fruitful engagement for the diaspora?

Higher education in Syria

The Syrian higher education system, like all sectors, has been severely affected by the conflict. A systematic review of the literature has revealed that the sector suffers from brain drain, inadequate funding, outdated curricula, low educational quality, fragmentation, extremely overcrowded classrooms, and teacher burnout. Another study indicated that the sector was used as a means of political control and indoctrination under the Assad government, completely undermining its independence, academic freedom, and civil society. Undoing the damage the Assad government has done to the sector requires the efforts of all stakeholders, including the diaspora academics. There is no accurate estimation of how many academics there are in the diaspora. In 2017, the Minister of Higher Education reported that 20% of academics had left the country, whereas the dean of the Medicine Faculty reported 30%. Other reports and studies estimated that between 1,500-2,000 university professors have fled the country, whereas others estimated that one-third of the country’s professors have left. These different groups of academics now constitute a new layer in Syria’s transnational intellectual communities and diaspora.

The potential role of the academic diaspora

Through my four years of research on this topic (PhD, unpublished yet), I found that diaspora academics perceive their potential role in shaping Syria’s future by supporting educational development across three interconnected levels: the student level, the academic level, and the institutional level.

On the student level, diaspora academics could supervise students, support the development of research skills at the Master’s or PhD level, assist prospective students in securing scholarships, aid language learning, and foster the development of academic skills. They may teach online or in person, run summer schools or courses, and conduct short workshops within Syria.

On the academic level, diaspora academics could support the professional capacity building of university lecturers by mentoring junior academics, organising visiting fellowships for Syrian scholars, co-writing and conducting joint research projects, assisting prospective teachers in securing PhD scholarships, running collaborative events with local academics, and supporting the accreditation of academics (e.g. advance fellowship).

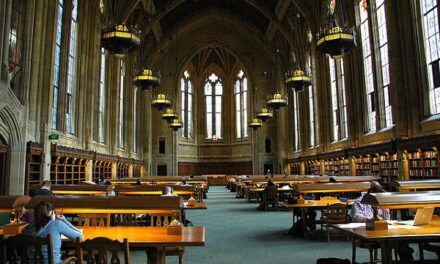

Regarding the third level, the institutional capacity building level, the academic diaspora could support libraries in Syria in accessing academic databases and publishers, developing university policies, building partnerships between Syrian and UK universities, supporting the governance of the education system, enhancing the technological infrastructure, establishing a welfare system for students and teachers, building laboratories, developing university curricula, creating Master’s programmes, and devising assessment methods.

Essential requirements for diaspora engagement

The question of what the academic diaspora can achieve is relatively straightforward. However, the question of how is considerably more complex. Through working the past 10 years on mobilising the Syrian diaspora and researching diaspora engagement in education development, I observed three preliminary requirements that serve as a starting point for directing the academic diaspora’s capacity towards Syria and translating this capacity into tangible work on the ground. One requirement originates from the diaspora, the second comes from the Syrian government and the higher education sector, while the third arises from international actors.

For the diaspora, academics need to organise themselves into groups, research clusters, regional networks, platforms, organisations, and so on. This could be a crucial step to amplify our capacity, mobilise resources, and institutionalise our work. Some academics in the diaspora have already worked over the past few years to organise themselves to realise their potential more swiftly. Some examples are the Syrian Academics and Researchers Network in the UK and the German Syrian Research Society. These organisations have adopted a strategy to build their institutional capacity, networks, and legal standing to be prepared when the window of change opens in Syria. More diaspora networks are currently beginning to organise themselves. I recently observed on social media the establishment of the Syrian Science Council and the Syrian Technocrats Network.

Within the country, the government and higher education in Syria could benefit significantly from the academic diaspora by establishing specialised departments or entities that act as points of contact between diaspora organisations and educational stakeholders. They could meet with the diaspora organisations, discuss projects, create schemes, eliminate barriers, organise efforts, and channel the capacity of the diaspora. Such entities and departments could play a significant role in harnessing the energy of the diaspora and institutionalising their contributions. At the time of writing, one of the major questions that some of the diaspora groups to which I belong are trying to answer is, whom do we contact to express our readiness to support? Having such entities would remove a crucial barrier to our engagement.

The temporary government in Syria is currently addressing extremely critical issues that may take precedence over establishing connections with the diaspora. Such matters include restoring order, integrating armed groups under the army’s umbrella, reactivating vital institutions such as the police, court system, and ministries, and drafting a new constitution that guides the country towards a peaceful Syria. At some point, the new government in Syria will possess a greater capacity to engage with the diaspora in a more institutionalised manner.

For international actors, they could support diaspora organisations in becoming development partners. This could involve funding organisational capacity building and projects that connect the diaspora with institutions within Syria. Over the past 13 years, international actors have displayed very little interest in such efforts because, understandably, having a dictatorship in Syria restricted any development initiatives. As the horizon now presents significant potential for Syria, international actors can assist diaspora organisations and local institutions in establishing partnerships that respect local ownership and culture and allow Syrians to take control of the development efforts.

In conclusion, the academic diaspora holds immense potential to contribute to Syria’s educational development across multiple levels: enhancing student skills, strengthening academic capacities, and supporting institutional frameworks. However, realising this potential requires concerted efforts from various stakeholders, including diaspora academics themselves, the Syrian government, and international partners. By fostering organised networks within the diaspora, establishing effective communication channels with Syrian educational institutions, and securing supportive measures from international actors, tangible outcomes can be achieved. As the situation in Syria evolves, creating robust collaborations and leveraging the expertise of the diaspora will be essential for driving meaningful educational reform and ensuring a brighter future for the country’s youth.